Harry Berger, Jr., Some Thoughts on his Passing

Thursday, Mar 25, 2021

“What a crock!” I remember declaring categorically, two weeks into my college career at UC Santa Cruz, as my Cowell College Western Civ core course break-out section had taken to tackling The Republic. “No wonder Socrates always wins these arguments, the guys he’s arguing with are a bunch of morons—‘Yes, Socrates, you are right, it must be so’ when it obviously needn’t be so at all—what total bullshit, the game is completely rigged!” At which point our section leader, lit professor Harry Berger, carefully took my measure and mildly observed, “But the thing of it is, Mr. Weschler, Plato was a genius and you are a freshman, and he is playing you like a fiddle: maybe you should just quiet down for a moment and listen to the music.” Nobody had ever talked to me like that. “Does it occur to you,” Harry continued, “that as far as Plato was concerned, the tragedy of Socrates’s life was that he never met an interlocutor worthy of the discourse he was trying to pursue, and that Plato was casting these dialogs of his off into the future in the hopes of maybe being able to find some, and that in fact you yourself could be one such, but only if first you learn how to read.”

Not a bad lesson, the first couple weeks of into a college career, and hardly the last that Harry would impart to me over the next several years.

“You actually wrote those words down,” my longtime friend and Berger seminar co-veteran John Wallach texted me, incredulous, the other day when I shared the anecdote with him soon after our hearing of Harry’s passing, at age ninety-six, “or is that just your Platonic reconstruction of Socrates?” To which I replied (I’d like to think in classic Harry fashion), “EVERYTHING is our Platonic reconstruction of Socrates, or at any rate our Socratic reconstrual of Harry. That at any rate is how I recall it, which is to say call it back forth, back and forth, how over the years I have taken to recalling recalling it.” To which John averred, “Gotcha.”

First we had to learn how to read. And there was always more to learn—or so I’ve found in the decades since (that first instance having been, hard to believe, already over fifty years ago now) as, deep into my own career as an itinerant reporter, I continued to commune with Harry, occasionally in person, more often by telephone and more frequently yet, especially more recently, across the page as his once hesitant commitment to booklength publication erupted into a veritable late-life surge (indeed three months ago he was telling me how he still had two more volumes actively in progress, I wonder if he finished them).

To read close and deep and actively, dynamically, in a continuous, open-ended, dialectical dance with the text. Consideration and reconsideration, hazard and hesitation, inspection and circumspection, vision and revision. He was a master of second thoughts, and third, and fourth. Forth and back, alone but then, thrillingly too (seemingly his favorite) in the company of others (“the pursuit of truth in the company of friends,” of course, having been our motto there at Cowell), the younger the better.

And the marvels he could worry out of a text! I once saw him give a ninety-minute lecture on an eight-line poem of Robert Frost’s, a dizzying dazzling roller-coaster of an interpretation, to the stunned (albeit somewhat intimidated) awe of a class full of freshfolk. And such a range of texts—Spencer, Shakespeare, Milton, Marvell, of course, but Plato, Dante, Theocritus, Beowulf, Pepys, Wordsworth and, yes, Frost, too. And not just texts, because he was a master at reading paintings, too: Da Vinci, Rembrandt, Vermeer, the Dutch still life masters, even Alice Neel. Deep looking: the slow reveal.

Have I mentioned how central this way of reading—texts and paintings—would prove in the development of my own capacities as a reporter: how one learned to read actual situations in the world, or the metalayers of the interactions with the subjects of one’s profiles?

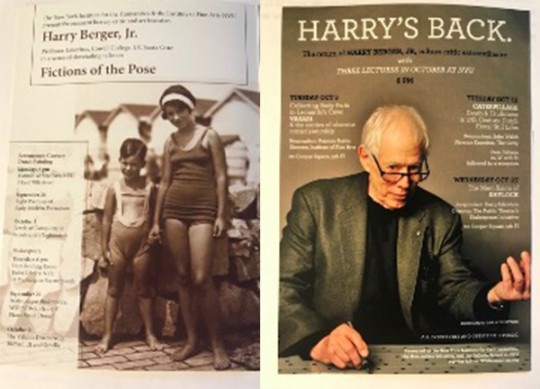

Fictions of the Pose: the title of just one of his books. The ever-tumbling contest, that is, between the painter and his/her subject for command of the representation of self (and whose self? the painter’s or the subject’s? especially when one is dealing with self-portrait). Sure, the book is utterly revealing when it comes to considering Rembrandt and Lotto and Branzino–but really, it ought to be required reading in any journalism course.

I am looking at the book now, there on my Harry Berger shelf. But the others, too, and how they each summon forth a whole world of associative suggestions. Second World and Green World: Studies in Renaissance Fiction-Making (the first as it happens in that late publishing surge of his, back in 1988). “Utopian misanthropy,” I remember from that one. But “conspicuous exclusion,” too, how Vermeer in this instance was able to render themes even more palpably and urgently present precisely as felt absences than if he had offered them forth outright (yet another insight especially useful to the budding reporter). Imaginary Audition, his book on Shakespeare on stage and on page—a response, perhaps, to the objections that would sometimes arise in seminar as he led us deeper and deeper into the extraordinarily supple and convoluted and contradictory ways characters interacted in the plays (“Surely,” we would protest, “Shakespeare cannot have meant all of that?”)—his response being (apart from, Whyever not?) to encourage us to become as-if directors of our own stagings in our heads as we read.

The titles, too, remind me of how funny Harry could be: sly, wry, quizzical, but then just gleefully silly. Caterpillage being the title he gave to his remarkable set of reflections on seventeenth century Dutch still-life paintings—you know, that endless succession of seemingly innocuous floral studies most museum goers just stream past on their way to the real star-turns somewhere up ahead, which Harry reveals, upon closer viewing, to be limning scenes of harrowing (albeit diminutive) carnage, rot, and devastation. Or his study of “Skills of Offense in Shakespeare’s Henriad,” which he winkingly, winningly titles Harrying.

Aye, how we are going to miss him. But then again not, since he remains so vitally present—that voice, the ever-penetrating insights, those gleams, that laugh—in the volumes he left us.

And, when it comes to Harry, it’s never too late to start. As an opening sampler, for still fresh beginners, perhaps try these two pieces which I managed to smuggle into a pair of more general journals in my sometime role as contributing editor. The first on Alice Neel of all people, and the second, on Rembrandt’s Night Watch, which begins, with typically Harry panache, “You go to the museum and you see this huge Thing staring you in the face and there doesn’t seem much you can say or feel about it except: Wow!” except that he thereupon proceeds to unfurl all sorts of fresh things you may never have noticed, for starters, the fact that a rifle is going off right there in the middle of the painting, just behind the dandy lieutenant’s ostrich-plumed hat. Who knew? Harry knew, or at any rate, he knew how to find out.

https://believermag.com/fictions-of-the-pose/

https://www.vqronline.org/vqr-gallery/supposing-rembrandt’s-night-watch