An early overview of the Getty in LA

LA Times Magazine | Sunday, Dec 07, 1997

Published as Before the Bulldozers in the Los Angeles Times on December 7, 199

Once Upon a Time, the Campus Was Simply a Great Place to Hike. Here's How One Local Boy Has Come to Grips With the Transformation.

I wasn't particularly predisposed to find myself liking the Getty. You might say I came to it with a certain chip on my shoulder--nothing, mind you, anywhere near as humongous as the one the Getty trustees seemed intent upon planting astride the shoulder of what had long been my single favorite Southern California mountain ridge. For years as a teenager and a young man growing up on the Westside, I used to head up to the nearby Mount St. Mary's College parking lot and launch out across the wending dirt trails and fire roads through the parched chaparral underbrush to that magic outcropping with its awe-inspiring vista--the entire expanse of the city from the distant mountains to the gleaming sea laid out before you, so close you felt you could almost reach out and touch it, and yet eerily, totally, silent. It was my own sweet little secret--mine, and that of maybe hundreds, probably thousands, of other secret sharers.

So you can perhaps imagine my dismay, over the past decade, at watching that exquisite, exclusive retreat disappear, as it were, beneath the scaffolding, only to reemerge, over the last several months, as this awkwardly looming, heavily laden, monolithically squat behemoth . . . this, (what?), this Toltec Nordstrom's.

Nor were the origins of the extravaganza all that edifying to contemplate. As founding patrons go, billionaire oilman J. Paul Getty's profile was hardly the most savory. Equally notorious as a miser and a womanizer, Getty was the sort of ruthless business operator ("When I'm thinking about oil, I'm not thinking about girls") who, during the Depression, fired all of his employees so he could rehire them at considerably lower wages.

One of his greatest passions as a collector was for 18th century furniture--the accouterments, that is, of privilege in the good old days of the ancien regime, before the rabble ever got it into their wee little heads to start entertaining such notions as the Equality of Man. An ardent admirer of Hitler through much of the '30s, he raced to Vienna in 1938, in the wake of the Anschluss, and managed to wheedle his way into the splendid home of Baron Louis de Rothschild (the baron himself having fallen under Gestapo detention), appraised the baron's exquisite furnishings and then rushed over to Berlin to sound out the SS on a possible deal, eventually procuring a pair of exquisite secretaries at a steep discount. (As he always liked to boast, "I buy when other people are selling.")

Declared the world's richest man in a 1958 Time magazine cover story, he nevertheless managed to avoid paying taxes almost entirely through most of the '60s, in part through a canny series of art donations, in many cases to his own museum.

I used to wonder what that marvelous Weimar aesthete Walter Benjamin would have made of Getty's hoard (especially had the celebrated Marxist belletrist survived that Nazi onslaught and--who knows?--made it to Southern California, like so many of his emigre contemporaries). Benjamin cherished antiquarian troves of all sorts, but he also had a fearsomely penetrating grasp of their inevitable underpinnings. As he once noted, "A historical materialist views [all cultural treasures] with cautious detachment. For without exception the cultural treasures he surveys have an origin which he cannot contemplate without horror. . . . There is no document of civilization which is not at the same time a document of barbarism. And just as such a document is not free of barbarism, barbarism taints also the manner in which it was transmitted from one owner to another."

Getty liked to proclaim that "an individual without love of the arts is not completely civilized"--which may be so, though its seeming corollary, that ostentatious love of art can certify a person's complete civility, is decidedly less self-evident. Getty's lavish bequest, at any rate, seems to have been at least as much a dodge (to keep the bulk of his millions out of the hands of his heirs, ex-mistresses and, especially, the government) as it was an expression of any love of the masses ("The meek shall inherit the earth," he once famously intoned, "but not the mineral rights!").

And yet the very open-endedness of that bequest--the trustees' having been constrained by its terms to further "the diffusion of artistic and general knowledge" (and that's pretty much it)--has facilitated a remarkably large-hearted transmutation of the old man's original intention (or, at any rate, of his famously pinched character). "Getty was doubtlessly an autocrat," as Harold M. Williams, the Getty Trust's president since 1981, five years after the billionaire's death, recently commented to me. "But he had the wisdom to know that when he died, he died." And generosity of spirit, general civic openness, vividness of engagement and an unexpectedly light touch have all been hallmarks of Williams' sunny, though soon-to-end, tenure.

There's been some carping over the seeming scandal of so much money being lavished on an institution devoted exclusively to the humanities (as opposed to, say, technological or medical innovation), but it seems to me that Williams' response, when I raised the issue with him, was exactly right: "I defer to no one in my admiration for the achievements of science and technology, but people also need to be reminded as to the limits of that kind of knowledge and the values that have to undergird it, which is what the humanities, broadly speaking, can and, indeed, urgently need to provide us with today." The humanities, "broadly speaking," he elaborated, were the lure that drew him to the job in the first place. The center wasn't simply going to house a magnificent museum, the trustees assured him. There would be all sorts of opportunity for institutional innovation alongside that--for the creation, as things developed, of state-of-the-art institutes devoted to conservation, information technology, education and research, all of which have been helping to weave the Olympian and potentially elite center back into the wider world.

The British-based Getty himself never even visited his Malibu villa museum, but the Getty Center has been making a concerted effort at being both in and of the city it so clearly looms above. The Conservation Institute, for example, with its ambitious projects flung from Quito to Cyprus to the Dunhuang oasis on the edge of China's Gobi Desert, is at the same time moving to rescue a unique David Alfaro Siqueiros mural on a second-story exterior wall on Olvera Street.

Even the Research Institute, with its focus, generally speaking, on the High Tradition, is hardly oblivious to the pull of the city. "We don't take the attitude," its director, Salvatore Settis, assured me, "of what we can teach L.A., but rather what we can learn from it." It is an altogether sensible approach, given the sort of world-microcosm the city (with its hundreds of distinct linguistic, cultural and ethnic groupings) has steadily been becoming. This year, for example, the Research Institute has brought together scholars from all over the world to focus on "Representing the Passions"--and yes, they will be delving into Attic tragedy, Elizabethan drama, and Japanese Noh plays, but they'd be fools to ignore either Hollywood or O.J., and they won't.

As for the physical plant itself, Richard Meier's hilltop monolith: As I say, heading up for my talks with Williams and Settis, I approached the place with certain trepidations, and, indeed, at first my reactions were decidedly mixed. I liked being able to leave my car down below. I loved the tramway up--its leisurely pace, the sibilance of its stately procession. I hated the blindingly white, antiseptically modern arrival plaza--a sweltering griddle on the not-all-that-hot day I happened to be visiting (and I sure wouldn't want to have to ford it in a gusty rain). Somebody next to me commented that she wished she could secure the eventual straw-hat concession (Hell, I replied, I wished I could secure the NASA spacesuit concession!). Nor did I much fancy the wide, sharp-edge Eisensteinian steps leading down from the museum on the far end of the plaza.

In general, I found myself hankering forlornly after a generalized sense of the place: Monolithically massive and yet still somehow amorphously indistinct from down below, the center seemed no more succinctly defined, as a single entity, up above. It seemed to spread in all directions; and for all the intellectually discernible coherence of its play of lines and arcs, there was no signature vantage, no singular impression of the place as a whole. By contrast, think (perhaps unfairly) of the Acropolis in Athens; or (more provocatively) of Frank Gehry's new Guggenheim building in Bilbao; or (for that matter) of Mount St. Mary's across the ravine. I assure you that, as an integrated entity, Mount St. Mary's looks a whole lot better from the Getty than the Getty looks from Mount St. Mary's. (No wonder Meier, with his sight lines, keeps on keying off the campanile-capped college--as if to appropriate its sense of itself as a Tuscan hilltop village, if only by association.)

And yet, it was strange, for as the hours of my visit stretched on, such querulous mutterings seemed to fall by the wayside, because--you know what?--the place is really just flat-out wonderful. Meier's splendors, it turns out--and they seem to rise up on all sides--tend to be intimate ones: this particular sight line, those uncannily counterbalanced volumes, that exquisite little nook. There's that same breathtaking panorama I so lovingly remember, but somehow even more sublime for being framed, momentarily withheld, and then divulged all over again, though from a freshened angle.

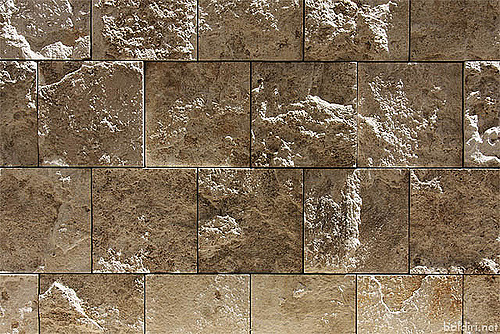

And then there's the travertine--Meier's positively genius-flecked inspiration of cladding vast swaths of his exterior walls with 2.5 foot square panels of raw Italian travertine--not smoothed or polished the way you would find it in the antique fora or Renaissance plazas around Rome, but rather cracked open, geode-like, to reveal the manifold splendors within. Manifold being the key word here. Every panel is different, expressing its unique geomorphological history and personality: Some of the squares seem sudsy, others all gritty and granular. There are foamy panels and slurried ones; some cusp the fossils of perfect leaves and one even palms the impress of a feather! Lined up like that, one beside the next, utterly regular and yet each one distinct, catching the light and changing with the passing hours (flat-mat to chiaroscuro, dusty beige to honey gold), they are like nothing so much as a metaphor for throngingly varied humanity itself.

And, of course, they just provide the shell. Beyond them comes the museum--for most visitors, probably, at least at the outset, the principal destination. And Meier's museum is well-nigh perfect. Its five two-story buildings are grouped around the reflecting pool of a central courtyard, and a typical transit through the second-floor galleries will take you from one exquisitely proportioned, perfectly sky-lit room to the next and then suddenly outside, across an exterior walkway with its momentary panoramic exaltation, before delving you back indoors for another sequence of peace-drenched rooms. Again, to make the comparison with Gehry's Bilbao achievement: By all accounts, the transit through Gehry's museum is positively pulse-quickening--the place is virtually carbonated, all fizzy with jostling vitality. Meier's, by contrast, is tumult-stilling, inviting (almost compelling) visitors to shed any superfluous exterior agitations. The spaces are splendidly serene--a long, cool drink from a deep, clear spring.

As for the collection, the downstairs galleries are given over, largely, to Getty's trove of palatial furnishings and decorative arts that, as you may have already gathered, I can frankly take or leave. Nobody who wasn't alive then, Talleyrand famously sighed, will ever be able to grasp the sweetness of life, before the Revolution. Perhaps, but by the evidence of Getty's collecting, such sweetness must at times have tended to verge on the cloying.

Upstairs, though, Getty's notoriously spotty core paintings collection has grown exponentially in both size and quality under the graciously judicious (albeit fabulously endowed) stewardship of John Walsh, the museum's director since 1983. The scale of the collection is now something like the Frick's in New York (though the quality, of course, is not yet up to that standard and probably never quite will be, absent the unlikely sudden appearance of three or four Vermeers on the open market), and the experience of a visit is likewise similar. One isn't overwhelmed by the sheer mass of material, which in turn allows one to be overtaken by single individual works (and different works, one suspects, each fresh time). The elder Jan Brueghel's deliriously common-sensical "The Entry of the Animals into Noah's Ark," complete with decidedly dubious onlooking neighbors, for instance, the most recent afternoon

I went ambling; Rembrandt's portrait of a startlingly contemporary St. Bartholomew (part of Getty's own original bequest, as it happens, so go figure); Edvard Munch's hauntingly brooding "Starry Night" (Van Gogh, as it were, as re-envisioned by Rothko); and then (happy surprise--a recent acquisition) David Hockney's photo-collage masterpiece "Pearblossom Highway," a virtual debauch of clear-seeing.

Back down in the lowlands during the weeks after my Getty visits, coursing along the freeway or wending among the leafy Brentwood side-streets--I'm sorry, I was still having a hard time dealing with that hilltop monolith. I was reminded of reporting visits I used to make to Warsaw in the bad old days of the Communist hegemony--how everybody wanted an office in the massively looming Stalinist Palace of Culture. And why? Because of the view: It was the only place in town where you didn't have to see the Stalinist Palace of Culture.

And yet that's not fair. The Getty from below is hardly that bad--and, in any case, it's already changing. Those Toltec ramparts: Wait a second, those are the luscious travertine panels--and already my heart is starting to melt. I make out individual balconies or balustrades, projecting in my mind's eye the magnificent vistas afforded by each particular vantage. And I have to smile: The place is growing on me and shows no sign of stopping.

SaveSave