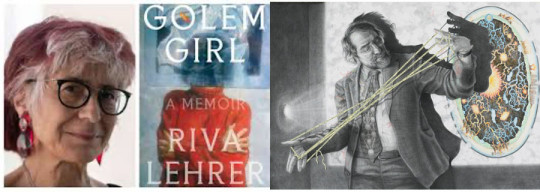

On artist and disability activist Riva Lehrer

A contribution to Lehrer's new memoir Golem Girl | Sunday, Nov 08, 2020

So here’s how Ren blurbed the book:

Oy, what a story: Job, eat your heart out! In Riva Lehrer’s life chronicle,

an appalling fate (and I don’t just mean the circumstances of her birth)

gets visited upon an invincible character, and the result is a wincing-wise

tale, by turns harrowing and hilarious, cut clean through with flecks of

grace and beauty. Lehrer is one wry mensch, and an extraordinary

kinstler to boot.

Earlier on, Lehrer (who was born in 1958 with spina bifida, almost died several times in those early years and many times thereafter and yet not only survived but thrived as an artist, activist, anatomy professor, and now a writer) had asked Weschler to provide an account of their original meeting and his subsequent experience of being portrayed by her, to be included among other such accounts in an after section of her book, and Weschler provided the following:

April 2019

“And what have we here?” I found myself thinking the first time I met Riva. Not “who?” as she would no doubt (and—okay, already—rightly) point out, but “what?” This corkscrew fireplug, this Lautrecian spitfire.

It was, as I recall, at the tail end of one of the events I had curated for the Chicago Humanities Festival in my role as its artistic director (a conversation with Philip Pullman, perhaps) and she just up and cor- nered me with comments and thoughts, and I was happy to invite her out for coffee: she veritably exudes charisma and resolve. But very quickly the what gave way to who, for the point is that what this who emanates more than anything else is heart, which is to say, Coeur, as in courage, not just in the physical fact of her ongoing existence, but in the heartening vigor of her presence, her way of being in the world, a sly wry gleam, which in turn gets refracted in the quality of her eye and hence her art.

So, anyway, what, she now asks me, was it like to sit (or as it happens, stand) and pose for her? Well, it was a continuation of what it is like to be with her more generally (I can’t really say I recall which part was the posing). Which is to say a fast and funny and often feisty exchange of views and convictions (I tease her a good deal and she gives as good as she gets) (we argue some, mainly around my exasperation at what I sometimes take as her insistence on certain political correctnesses at the expense, I feel, of more free-flowing immediacies—and, again, she gives as good as she gets, which is what makes it fun). We talked about how I might like to be portrayed, it was a spirited negotiation (that makes it sound more con- frontational than it was, for it was more of a harmonizing improvisation, a meeting of her sense of me and my sense of myself, I suppose), and we hit on various themes, my taste for marvel (as evinced by my ironical veneration of Athanasius Kircher, the great seventeenth-century Wondercabinetman, Jesuit keeper of the Vatican collections and compiler of every odd thing on earth and inventor of all sorts of marvels, not least including the slide projector, the last Man Who Knew Everything—from acoustics through volcanology on out to the interpretation of Egyptian hieroglyphics—even though he was wrong about a lot of it, though not always so [viz, the slide projector (in the seven- teenth century!)]; and likewise my sometime orientation toward the Kabbalistic) and her sense of me as some kind of whirling dervish, a generator of sidewise connections (among ideas and people and occasions), hence the cat’s cradle (for which she commandeered and sliced up a sheet of yellow legal pad raw copy from a piece I once wrote about, I believe, Poland). And she took me to one of her classrooms and had me sit, stand, pose, prance in the sidewise glare of a slide projector as she took dozens of photographic notes, and then same deal on the roof of her apartment building in the sidewise glow of the setting sun— arguing with me about this and that all the while, though it’s always hard for us to keep a straight face in our arguments (as I say, they just end up being too much fun).

And then she went off to her art burrow, I headed back to my own such burrow in New York, and the next time we reconvened, some months later, there I was, butterfly-splayed in the graphite-graphic splendor of her capture: a thing of marvel, if you ask me. She’d up and nailed me.