The Whitney in Black and White

Project Syndicate | Monday, Apr 24, 2017

Lawrence Weschler takes sides in the incendiary debate that erupted at this year’s Whitney Biennial over white artist’s depiction of the murdered teenager Emmett Till.

When the artist Dana Schutz depicted the murdered teenager Emmett Till’s brutalized body lying in an open casket, she did so in solidarity with the mothers of young African-American men killed by police officers in recent years. The subsequent attack on Schutz and her alleged act of cultural appropriation reflects the decadence of a once-valuable discourse.

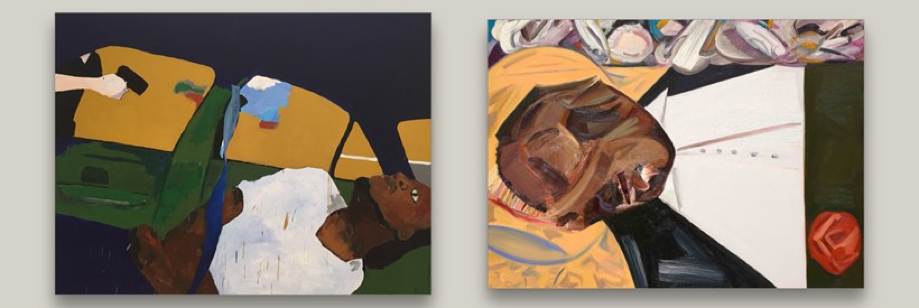

NEW YORK – Take a look at the two paintings above. Both draw on iconic photographic images from the ugly and fraught history of race relations in the United States, and both are among the most discussed works featured at the current Whitney Biennial at New York City’s Whitney Museum of American Art.

The painting on the left is by a white artist; the one on the right is by an African-American. And that has made all the difference in how the two paintings have been received: the one on the left has become the center of a furious controversy. Soon after the show opened last month, Hannah Black, who identifies herself as an “Artist/Writer” and 2013-2014 Critical Studies fellow of the Whitney’s Independent Study Program, launched a petition drive (supported by dozens of her fellow artists and writers, both black and white) demanding that the painting be removed from the show. But the petition went even further, demanding that the painting be destroyed, so that it could never subsequently “enter into any market or museum.”

Although the artist’s “intention may be to present white shame,” Black conceded in her petition, “this shame is not correctly represented as a painting of a dead Black boy by a white artist.” Any “non-Black artists who sincerely wish to highlight the shameful nature of white violence should first of all stop treating Black pain as raw material. The subject matter is not [theirs]; white free speech and white creative freedom have been founded on the constraint of others, and are not natural rights. The painting must go.”

Art in Black and White

But wait. My mistake, excuse me: It’s the painting on the right, depicting the brutalized body of Emmett Till, a 14-year-old African-American boy who was tortured and killed by two white men in 1955, that is by the white artist, Dana Schutz. The painting on the left, depicting the immediate aftermath of last year’s unprovoked shooting by a Minneapolis police officer of Philando Castille (as captured by his uncannily poised girlfriend on her smartphone) is by a black artist, Henry Taylor.

What is true of both paintings is that the race of the artist is impossible to discern. Nonetheless, Black and her fellow petition signers have argued that the value and validity – indeed the very permissibility – of Schutz’s painting turns entirely on the question of her race.

As Black acknowledged in her petition, the painting depicts “Till in the open casket that his mother chose, saying, ‘Let the people see what I’ve seen.’” Till, who lived in Chicago, had been summering with relatives in Money, Mississippi, when he was abducted and gruesomely lynched for supposedly flirting with a white woman (a charge recently disavowed, over a half-century later, by the woman in question). The sight of Till’s battered body elicited widespread horror among whites and blacks alike at the time: his face, so badly pummeled that it had swollen to almost twice its normal size, was unrecognizable. The murder of Till, coupled with the previous year’s US Supreme Court school-desegregation decision in Brown v. Board of Education and the ensuing year-long bus boycott in Montgomery, Alabama, is often credited with triggering the civil rights movement that followed.

Black, however, goes on: “That even the disfigured corpse of a child was not sufficient to move the white gaze from its habitual cold calculation is evident daily and in a myriad of ways, not least the fact that this painting exists at all. In brief: the painting should not be acceptable to anyone who cares or pretends to care about Black people, because it is not acceptable for a white person to transmute Black suffering into profit and fun, though the practice has been normalized for a long time.”

And so forth. Never mind that Schutz has said that she returned to the Till photograph in her own anguish over the spate of police killings of young black men around the US in recent years. She had responded to the photo, she said, as a mother trying to empathize with the heartbreak and horror of all the mothers of all those boys and young men – and, in any case, she’d never had any intention of selling the painting that resulted from her reckoning.

Black is not interested in any of that. For her, Schutz’s identity, not her intent, must guide our aesthetic judgment. Her petition partakes of a kind of rhetoric and a form of critique that have been rampant in US art schools and universities for the last several decades, becoming more intensely strident with the passing years. One can recognize the intellectual terrain by its indigenous language, its mandarin speakers tossing around terms like “privilege,” “intersectionality,” “appropriation,” “postcolonial,” “gendered,” “cis-gendered,” and “gaze,” like so many worn-down tokens.

It is not that the general tenor of the critique is entirely without merit. On the contrary, the terms cited above started out as markers for issues perfectly worthy of respectable – and often bracingly pertinent – consideration. So what lies behind their degeneration into tendentious, kneejerk, weaponized clichés?

Cultural Truthers

According to the late religious historian Donald Nicholl, heresies in the early Christian church generally consisted in long-suppressed aspects of truth being elevated to the level of the Whole Truth and idolatrized as such – a problem not so much of verity as of proportion. In that sense, the current academic focus on, for example, the bankruptcy of the “privileged gaze” – and hence on who even has the right to speak about or on behalf of whom – can be considered heretical: it is conviction out of balance, righteousness untethered.

It is possible to imagine another way of thinking about these things – one once championed by the late James Baldwin. With every passing year, Baldwin, who died in 1987, seems to consolidate his position as the greatest, most prescient, and most urgently necessary voice of his generation of American writers. And what may be most salient today is the metastable “we” in his formulations, how he would glide back and forth between “we black people” and “we Americans” – a constant negotiation that came to animate his entire body of work.

Consider for example, this passage from the end of Baldwin’s 1964 essay “Words of a Native Son”:

“The story that I hope to live long enough to tell, to get it out somehow whole and entire, has to do with the terrible, terrible damage we are doing to all our children. Because what is happening on the streets of Harlem to black boys and girls is also happening on all American streets to everybody. It’s a terrible delusion to think that any part of this republic can be safe as long as 20,000,000 members of it are as menaced as they are. The reality I am trying to get at is that the humanity of this submerged population is equal to the humanity of anyone else, equal to yours, equal to that of your child. I know when I walk into a Harlem funeral parlor and see a dead boy lying there. I know, no matter what the social scientists say, or the liberals say, that it is extremely unlikely that he would be in his grave so soon if he were not black. That is a terrible thing to have to say. But, if it is so, then the people who are responsible for this are in a terrible condition. Please take note. I’m not interested in anybody’s guilt. Guilt is a luxury that we can no longer afford. I know you didn’t do it, and I didn’t do it either, but I am responsible for it because I am a man and a citizen of this country and you are responsible for it, too, for the very same reason….We must make the great effort to realize that there is no such thing as a Negro problem – but simply a menaced boy. If we could do this, we could save this country, we could save the world. Anyway, that dead boy is my subject and my responsibility. And yours.”

For Baldwin, the memory of Emmett Till lying in his casket belongs to – calls out to – all of us. Surely Till’s mother thought so as well, her intention clearly being to compel all of us – as blacks, as Americans, as fellow humans – to struggle, and to go on struggling, to come to terms with its urgent, bloated cry.

Post-Heretical Identities

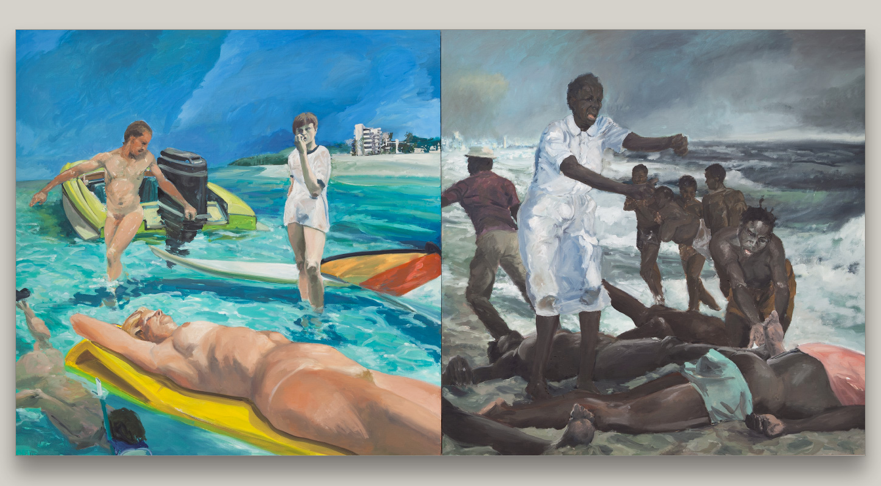

Just upstairs from the Biennial these days, the Whitney happens to be displaying a floor-full of paintings from the 1980s, among which appears a seminal and indelibly powerful diptych by Eric Fischl: his “A Visit to / A Visit from / the Islands” of 1983, occasioned by that year’s catastrophic flight of refugees from Haiti.

What might Hannah Black and her co-petitioners say about a painting like this? Would they argue that Fischl had the “right” to portray one side of the painting but not the other? Just how threadbare and sterile do they intend our common cultural discourse to become?

And, all the while, as the petitioners set fire to the carpet, the elephant in the room threatens to bring the roof down. While the mavens of critique gnash and rage and train their sights on fellow cultural workers, real racists and white supremacists are cementing their hold on the highest reaches of the US government.

I am reminded of the great poet and essayist Elliott Weinberger’s response to a similar moment, back in the early 1980s (not long after the original infestation of critique-driven distemper across American academia). Weinberger’s response took the form of an address to fellow poets at a New York convocation. He started by saying that he took “the word ‘politics’ in a very narrow sense: that is, how governments are run. And I take the word ‘government’ to mean the organized infliction or alleviation of suffering among one’s own people and among other peoples.” Not a bad definition, that. He continued:

One of the things that happened after the Vietnam War was that, in the US, on the intellectual left, politics metamorphosed into something entirely different: identity politics and its nerd brother, theory, who thought he was a Marxist, but never allowed any actual governments to interrupt his train of thought. The right however, stuck to politics in the narrow sense, and grew powerful in the absence of any genuine political opposition, or even criticism, for the left had its mind elsewhere: It was preoccupied with finding examples of sexism, classism, racism, colonialism, homophobia, etc. – usually among its own members or the long-dead, while ignoring the genuine and active racists/sexists/homophobes of the right – and it tended to express itself in an incomprehensible academic jargon or tangentially referential academic poetry under the delusion that such language was some form of resistance to the prevailing power structures – power, of course, only being imagined in the abstract. (Never mind that truly politically revolutionary works – Tom Paine or the Communist Manifesto or Brecht or Hikmet or a thousand others – are written in simple direct speech.)

Meanwhile, Ronald Reagan was completely dismantling the social programs of the New Deal and Johnson’s Great Society….

Weinberger was right then. Alas, he is no less right today, more than three decades later. Black and her fellow petitioners have raised some important points; but those points should be seen as an invitation to further consideration and engagement, not the foreclosure of all possible discourse. How should the harrowing be represented, and by what right, indeed?

Aime Cesaire, the Francophone poet, politician, and essayist who helped found the Négritude movement of the mid-twentieth century, once admonished his readers as follows: “Most of all, beware, even in thought, of assuming the sterile attitude of the spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of grief is not a proscenium, a man who wails is not a dancing bear.”

The question swirling around this year’s Whitney Biennial is just who is violating Cesaire’s dictum. Is it Schutz, with her heart-rending mental act of witness (the paint itself clotted high and gouged deep with anguished fellow feeling). Or is it the latter-day Saint-Justs and Robespierres, who would use her act of solidarity as the occasion for a spectacularly ill-tempered and ill-timed polemical exchange of their own?

###