Dogged by Trees

Artenol | Monday, Nov 07, 2016

I DON'T KNOW, maybe it’s something in the air, but when it comes to my interactions with the art world these past several years, I’ve been being dogged by trees (which, granted, is far better than its Django alternative, but still).

Some of you may recall Houston’s great Art Guys-Tree Wedding Kerfuffle of a few seasons back, in November 2011 to be specific. Oy, do I remember it, because, Reader, listen, I was the Rebbe.

Earlier that year, I’d been interviewing the Guys about something else altogether when they told me about how a couple years before that, at a time when Texas politicians were lashing themselves into a righteous lather over the prospect of gay marriage (how, in the inimitable stylings of Governor Rick Perry, if you sanctioned gays marrying each other, the next thing you knew you’d have people demanding to marry their dogs), the two of them had decided to marry a tree. They insisted, tongues lodged distinctly somewhere cheekward (though it was not entirely clear how deeply), that their gesture had nothing to do with Perry or gay marriage or anything like that, that if anything it nodded in an ecological direction. Anyway, they explained how back in 2009, since the sapling of their desires was still under age, they’d only gotten engaged (what kind of deviates did I take them for?), but that now that the tree in question had come of age, having reached sufficient height (ie, theirs), and now that they had secured the de Menil’s commitment to lodge the bride as part of its collections in its own lush groves, they were now intending to hold a full-on wedding ceremony that coming November, and would I be willing to help officiate. I informed them that I only entertained such official functions in my sometime-somewhat role as rabbi, and to their credit, they did not blink.

Little did I know, and probably little did any of us, but by the time November had rolled around, the impending ceremony had taken on the trappings of a full blown PC meltdown scandal, several members of the local gay constabulary having taken it into their heads that the Art Guys were making fun of them—the Houston Chronicle’s art critic at the time hyperventilating about the way the de Menil had allowed its hallowed name to become entrammeled in an assault on what was after all “the human rights issue of our time,” and at a sort of rally the night before the de Menil ceremony, they and their supporters gathered at a local gay strip club, where the critic in question (just in order to register the sheer extent of the outraged community’s umbrage) subjected himself in the time-honored spirit of civil disobedience to the ultimate sacrifice, as he put it: he married a woman. The celebrants were thereupon invited to fold that marriage’s announcements into (very sharp) paper airplanes and to reconvene the next morning at the Art Guys’s event.

Which is the scene into which I, as rebbe, now found myself lumbering that gray and drizzly morn, as several hundred officiants gathered on the DeMenil’s grounds, several dozens of those armored with (very sharp-looking) paperplanes. In the event, things went off quite peaceably. In my role as rebbe (and nobody even bothered remarking how in the spirit of the festivities I had taken to wearing a Palestinian kafia in lieu of the traditional Hebrew tallit)

I noted how powerful a thing it was to be reconsecrating this particular tree in the wake of the previous season’s record-shattering heatwave which had decimated a truly dismaying portion of the city’s other mature trees, and I went on to invoke the wisdom of my fellow Rebbes Donald Barthelme (from the dryad-man love story in his short-tale sequence “Departures”) and Rabbinahs Denise Levertov (her sublime poem “A Tree Telling of Orpheus” ) and Kay Ryan (her crisp short heartbreaker of a lyric, “Tree Heart/True Heart”); after which the wise and wizened veteran Houston art honcho James Surls got up and asserted quite simply that he’d known the Art Guys in question for decades and they were obviously not homophobes and the art world was way too small and itself way too threatened for this sort of thing and couldn’t we all just get along, at which point it seemed that those very sharp paper planes got stuffed back into pockets, the wedding ceremony proceeded to its conclusion, and blithe sanity seemed to have returned to the garden.

Till a couple of days later, that is, when someone (no one ever found out exactly who) went and assassinated the tree.

Or anyway, tried to. (The local media at any rate immediately took to referring to the Art Guys as “the widowers.”) And yet, somehow, the stunted plant survived. The De Menil, for its part, however, apparently freaked out by this latest turn of events, went and deaccessioned and now evicted the blasted tree-now-shrub, which had to be transplanted to a new home on a lot behind the Guys’s studio compound—though look at it now, three years on.

\

\

So: maybe that was one of those sorta happy life-(and the life of art)-goes-on sagas after all.

NOT SO ALAS. The next one. For exactly one year later, in November 2012, a disconcertingly similar train of incidents played out in England.

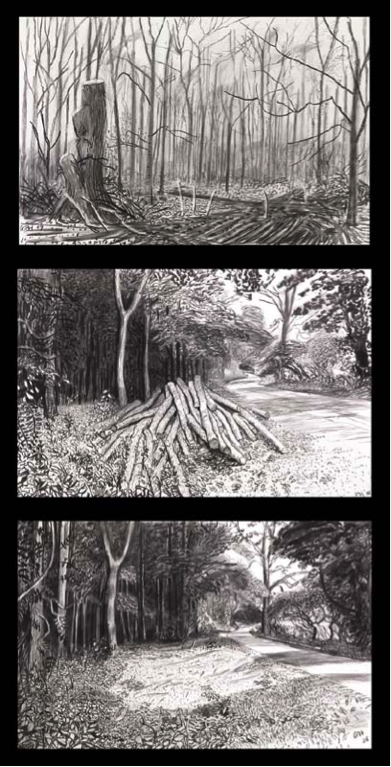

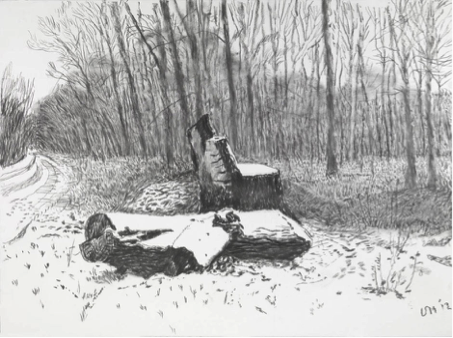

Earlier that year, David Hockney had been the subject of a record-breaking exhibition at London’s Royal Academy surveying his prior decade of work documenting the passing of the seasons in the immediate wheatfield and forest copse surrounds of his new home in the small resort town of Bridlington, on the Yorkshire coast facing out toward Holland, the very fields and forests across which he had traipsed as a youngster and then a teenage summer worker on outings from his hometown, further inland, of Bradford. Among the deliriously colorful oils and and watercolors and Ipad drawings were all manner of sketchbooks and pencil and charcoal drawings—the same scenes returned to again and again, at different times of day across different seasons in different media—and one series in particular of these last stood out for many people: a sequence of charcoal drawings documenting the thinning out of a particularly beloved stretch of woodland, the sort of clearing activity taken up every few years by the local foresters to insure the continued health of the forest. One couldn’t help but glean a deep sense of mortality across the images that poured forth across Hockney’s witness, however, especially when one kept in mind the terrible swath among his own cohort that AIDS has scythed over the preceding decades. And even more moving, in this context, was the stalwart survival of one particular tall stump, which Hockney had himself asked the foresters to spare, and which he now took to referring to as the Totem and began portraying again and again, across all manner of other media, in the months that followed, a sort of stand-in, one couldn’t help but feel, for his own weathered self.

In the months after the Royal Academy show, increasing numbers of tourists began trekking out to the two or three square miles outside Bridlington that some people began to think of as a sort of Hockney National Park, so immediately recognizable were that swerve of road, this specific hedgerow, that fold of wold, this forest path, and of course, that Totem. One day toward the end of that November, Hockney was felled by a minor stroke and ended up spending the first night of his seventy-five year life in a hospital for observation. During that night, as it happens, vandals attacked the Totem, slathering it with pink graffiti, the words “cunt,” caricatures of a cock and balls, some of the imagery arguably homophobic in nature. When David returned home from the hospital (his linguistic abilities temporarily somewhat slurred, though his artistic ones were completely unscathed), his studio assistants were afraid to tell him of the vandalism, but when he finally heard about it, he was surprisingly unfazed, noting that the coming winter’s storms would no doubt wash away the damage. \ A few weeks later he travelled down to London for a minor follow-up operation, and that night the vandals returned—it is assumed there were at least two, given the mayhem they wrought—and completely chopped down the already defaced stump.

This time, returning to Bridlington and getting told of the attack, Hockney was completely devastated. He couldn’t get over the sheer gratuitous meanness of the act, “The meanness of it all,” he kept muttering. He retreated to his bedroom for two days of grimly defeated desolation, after which he roused himself and asked his crew to drive him out to the scene, where over the next several days, he recorded a suite of five gorgeously devastated charcoal drawings as a kind of commemorative tribute. Getting wind of the attack, the editors at the Guardian, one of Britain’s premier newspapers, contacted Hockney for comment. He told them of the drawings and agreed to let them run a selection, which they proceeded to do, on page one, above the fold.

News that stays new…

I SUPPOSE TREES have been back on my mind even more so lately owing to a terrific little way-out-of-the-way show I happened upon several months ago, indeed one of the most memorable I saw all last year. It was a student show, or rather the product of a graduate exhibition practices curatorship seminar at the University of Illinois, Chicago, and was lodged in the University’s Gallery 400. I suppose I shouldn’t have been surprised at the enterprise’s quality given the fact that even though the curatorial process had been exceptionally collaborative, as the catalog detailed, it had been led on an adjunct basis by the South Africa-born Rhoda Rosen, one of the most dynamic and creative curators around.

The UIC exhibition was entitled “Encounters at the Edge of the Forest,” and set out to survey the work of a range of contemporary artists who’ve recently been taking up trees as their subjects, but not trees as conventionally portrayed, that is as pastoral emblems of nature unsullied by man—rather trees, as they have in fact become: contested foci for nationalist assertion and state formation.

As Rosen explained in her catalog essay,

Modern scientific forest management, first established during the eighteenth century, functioned to connect all aspects of colonial power. Although its origins lie in Germany, it is no coincidence that Dietrich Brandis, whose name is synonymous with the birth of forestry, worked for a decade for the British colonial administration in India where, as Dan Handel shows, the widespread implications of forest management for the colonial agenda were first played out. As Lord Dalhousie’s superintendent of teak forests in the Pegu region of east Burma and, later, as his first inspector-general of forests, Brandis was directly implicated in Dalhousie’s project to modernize India in order to bring it more efficiently under British control. Further, he was implicated in Dalhousie’s expansion of the area of British rule through the largest-scale colonial land grab to-date and to his endeavor to centralize communications in order to facilitate the military and economic exploitation of India’s natural resources.

Rosen goes on to note that the British brought similar politico-forestry zeal to their administration of Palestine, zeal which continued into the Israeli period (think about the millions of incongruously Northern European pine sapplings which were brought in, often to cover over evidence of once vibrant though now evicted Arab villages, and the generations-old indigenous olive groves which by contrast were often being eradicated in the process). The show’s name derived from the title of a novella by the Israeli writer A.B. Yehoshua, Facing the Forest, in which a failed Hebrew scholar, unable to find meaning in his studies, assumes the position of a watchman in a remote forest, where he is supposed to be on the lookout for arsonists. The only other person he encounters is a mute Arab farmer whose tongue was cut out by Israeli forces in the 1948 war, and who, by the end of the story, starts a fire before which the student decides not to intervene, watching as, burning to the ground, it reveals the ruins of the Arab village the forest had been concealing.

The genius of the show, however, was the way Rosen and her students were able to uncover similar sorts of tree deployments by artists working all over the world. Thus, for example, Ken Gonzales-Day’s gorgeously composed Ansel-Adamslike color photographs of magnificent solitary treestands from all over the United States

which turn out to have been the actual trees from famous earlier lynching incidents and their resultant souvenir photographs—an especially effective way of solving the problem of alluding to those photographs without engaging in the ethically suspect activity of colluding in the display of the actual dead body.

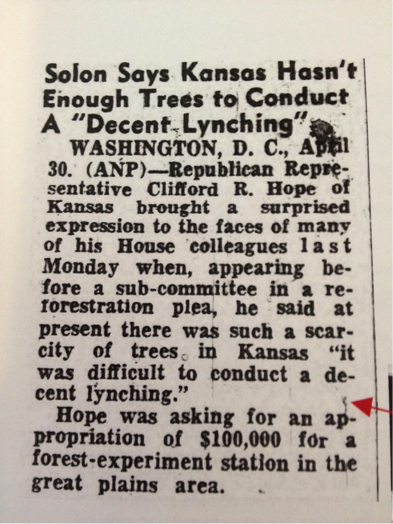

Along the same lines, one of Rosen’s students, Leonard Cicero, came upon and displayed the blow-up of a press clipping from the April 30, 1937 California Eagle, which details how—well, read it for yourself:

Elsewhere in the show, Rosen and her students displayed the video of a truly haunting 16 mm film by the Israeli artist Ori Gershi, taken in the Moskalovka forest in the Kosov region of the Ukraine, one of the last great such primieval forests in Europe, where Jews had hidden out at the outset of the Holocaust, until in 1942, over 2000 of them were discovered and murdered right there. In the film, the engrossingly serene beauty of the present-day forest is repeatedly sundered by the sound and sight of slicing, crashing trees.

The South African David Goldblatt was represented by his photograph of the “Remnant of a hedge planted in 1660 to keep the indigenous Khoi out of the first European settlement in South Africa,” a hedge which has in the meantime been transplanted to and flourishes in one of South Africa’s most renowned botanical gardens in Capetown, at the foot of Table Mountain (talk about the Pastoral Oblivious).

The Canadian Andreas Rutkauskas trains his lens on the bizarre “Cutline,” a clean slash of cleared out forest that now, in the wake of 9/11, runs the entire length of the US-Canadian border, to often quite surreal effect; while the Brit Phillipa Lawrence, for her photographs, swaths trees with the very barcodes of the lumber for which they are industrially destined:

Other instances got referenced in the show and its catalog as well, everywhere from Afghanistan to the Demilitarized Zone separating North and South Korea (where a 1976 joint US and South Korean mission, code-named Paul Bunyan, broached the DMZ in an attempt to “assassinate” a poplar tree that was blocking the view from an observation post, a mission which resulted in the deaths of two US soldiers).

But arguably the most affecting piece—and here we come full circle—was a videotape documenting the Israeli artist Ariane Littman’s intervention, just on the Palestinian side of the separation wall, where starting at dawn the artist approached the stunted remains of a once thriving olive tree in the middle of a traffic roundabout, and proceeded to start wrapping it in surgical bandages, an achingly caring and evocative process which lasted till that evening.

(The next morning, the catalog informs us, the bandages had all been stripped away.)

Rosen’s essay invokes “Unchopping a Tree” WS Merwin’s remarkable prose poem from 1970, the year of the first Earth Day, in which the poet launches out by suggesting we “Start with the leaves, the small twigs, and the nests that have been shaken, ripped, or broken off by the fall,” going on with truly haunting rigor to lay out all the steps, one after the next, that would prove necessary if we were ever going to succeed in righting the felled arbor. All manner of fixatives and heavy machinery are adduced across three pages of densely imagined prose, until

Finally the moment arrives when the last sustaining piece is removed and the tree stands again on its own. It is as though its weight for a moment stood on your heart. You listen for a thud of settlement, a warning creak deep in the intricate joinery. You cannot believe it will hold. How like something dreamed it is, standing there all by itself. How long will it stand there now? The first breeze that touches its dead leaves all seems to flow into your mouth. You are afraid the motion of the clouds will be enough to push to over. What more can you do? What more can you do?

But there is nothing more you can do.

Others are waiting.

Everything is going to have to be put back.

Put back indeed. Or at very least toured: it would be nice if someone would find a way to travel the University of Illinois students’s remarkable little exhibit. It deserved a far wider and longer place in the sun than it got.

SaveSave