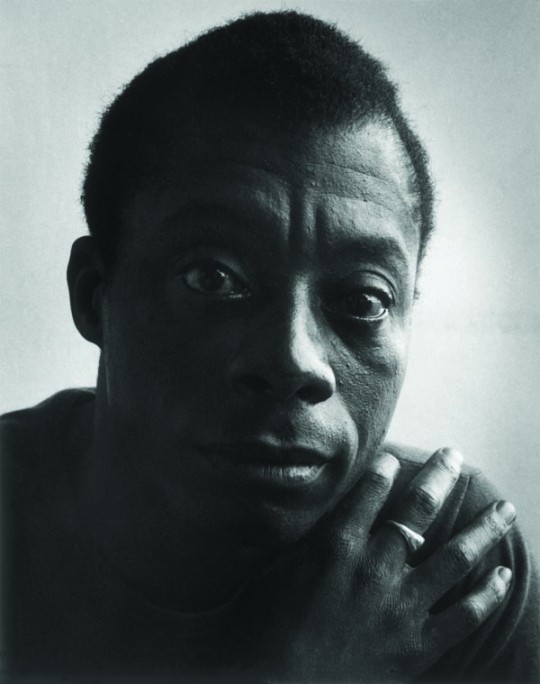

On James Baldwin

Brooklyn Rail | Sunday, Jun 01, 2014

In commemoration of the 90th anniversary of the birth of James Baldwin, New York Live Arts, Harlem Stage, and Columbia University School of the Arts are dedicating an entire year of programming to his life and work, which launches with the Live Ideas Festival, James Baldwin, This Time! at New York Live Arts later this month. Lawrence Weschler and Baldwin scholar, Rich Blint, recently visited the Rail headquarters, where they spent an evening discussing Baldwin, his enduring legacy, and relevance for our time.

Lawrence Weschler: Maybe the way to start is by relating how we have gotten to know each other over the last few months, which is that we are both working on James Baldwin. I’ve been working with Bill T. Jones on the Live Ideas Festival he started, which takes place once a year at his New York Live Arts (NYLA) dance space. We’re always trying to engage “embodied” ideas: it could be, body/soul, body/mind, body/spirit, body/politic. Last year, we did five days of Oliver Sacks: very body/mind. As we were trying to decide what to do next—it happens that I’m also on the Artists’ Circle of Harlem Stage—they were talking about a whole season devoted to Baldwin, and it suddenly occurred to me, “Let’s bust this thing open and do a whole year devoted to Baldwin.” And in fact, that’s just what’s going to happen. We are going to do The Year of James Baldwin. And we’re going to launch it this April 23 – 27 at NYLA: Five days, 20 events, under the rubric “James Baldwin, This Time.” But as we got going, the name that kept coming up was yours: you, Rich Blint, are at the School of the Arts at Columbia University. So now it’s a partnership between the three of us (NYLA, Harlem Stage, and Columbia) to do this James Baldwin project.

I suppose, maybe I’d start by noting that you are really a Baldwin person. I just play one this month, but you are the serious thing. How did that happen with you?

Rich Blint: Baldwin came into my life pretty early on. I was an honors student at John Kennedy High School in the Bronx reading Homer, all the “big” books, and devouring them in a certain kind of way, but in many ways not feeling—I mean, it’s not about re-presenting or identifying myself. It isn’t anything that “simple.” It was more about the fact that I didn’t see a certain kind of witnessing in those books of the world that I inhabited and the things that concerned me. And so I started reading and building my own library. This is when I was around 16 or 17 and I was, like, “Who is this man?!!” I read Morrison, Wright, and Hurston, and of course they’ve all stayed with me. Baldwin in particular stayed with me as a gay man, a black gay man. That was important.

Weschler: Which was clear to you already then?

Blint: Yes, at a very young age. You know, sexuality is fluid and all that kind of stuff. But I wanted to honor a certain kind of desire that I also found in his work. Giovanni’s Room is very important to me, and that book doesn’t even have any black figures in it, so it’s not simply about mirroring or identity. It’s more about—maybe the word is witnessing—Baldwin, in all of his writing, both the fiction and nonfiction. I refuse, incidentally, and I’m not being lazy here, to indulge those foolhardy, generic divisions that say, “Oh, his essays are the best and his novels are nothing.” The novels … he’s telling stories in all those places. In the poems, the nonfiction pieces, the interviews, the plays.

Weschler: What did you read first?

Blint: Go Tell It on the Mountain. Actually, honestly, “Sonny’s Blues,” in class, which kept coming up. So “Sonny’s Blues” was the first thing that I read which was mind-blowing. To be honest, when I first started reading it, I had been in the country for four years by that time.

Weschler: What do you mean? What’s your background?

Blint: I was born in Kingston, Jamaica, and I came to New York, the Bronx in ’84. And all the things that we were told in the Caribbean about New York, “The streets are paved with gold,” there’s a certain kind of future guaranteed, were not at all what you found in a crack-ridden—well we weren’t in a crack-ridden area, but it was an incredibly intense time in the city. So I read “Sonny’s Blues” first, for sure, and then Go Tell It just changed my life. It possessed me, this, again, the word is that “telling” of a complex tale. It also gave me a certain kind of self-possession. His moral imagination, his insistence on witnessing the real history we all share; “our common disaster,” a favorite phrase of his, gave me, not hope, but clarity about the world. And it gave me this incredible moral sense that is unwavering in me to this day. So, the vagaries of everyday life, professional life, and personal life for me are guided by that really central place of asking, “How do you move in the world in relationship to each other, to institutions? What are you going to do while you’re here?” That is what Baldwin brought home to me.

Weschler: Was Baldwin somebody a lot of people read in high school? One of things I wanted to talk about about is that I think, very strongly, that of that generation of writers—and that’s the generation that includes Styron and Capote and Mailer and Roth and Updike—it seems to me that Baldwin, today, is the most urgent, the most salient, and by the way, as gorgeous a writer as any of them. He has his finger on the American essence, on all this stuff that is so profoundly mysterious and messed up about America—American exceptionalism, race, class. He really looked at it, and not just as just a black person or as a gay person. The phrase he kept going back to is “as an American.” It’s really interesting because he flees America in the late ’40s. He runs away to save his life. He says he would have died if he’d stayed. And he goes to Paris. And it’s in Paris that he discovers himself “as an American,” as distinct, for example, from all the African Négritude writers who were there.

Blint: What he says is: “You take your home with you, otherwise you’re homeless.” He was fleeing the menace of America’s relationship or orientation to black people, and black men, specifically, and he felt it, in that grand, New Testament style—the junkies on the street, the drugs, the prostitutes, and all that stuff was and is true. We see many of those outcomes all the time. After his father’s death, he knew his mind could save him and that’s why he left, and as he said repeatedly, he just landed in Paris. He could have gone anywhere; he just wanted to get out.

Yes, he wrote as an American, but an American who didn’t believe in the myth of America—an American who understood that America was an incredibly young Republic, a project, an experiment founded in fire. That’s the crucible.

Weschler: It’s not lazy American patriotism by any means.

Blint: That’s not what I’m suggesting at all, but I think it’s important that we parse what he means by we have to “achieve our country.” As Stuart Hall says in the British context: “that unfinished conversation.”

Weschler: I’m getting at the use of the word “our” in that sentence. The “our” in that sentence is not, “we gay people,” “we black people.” It’s “We Americans have to achieve our country,” which is what is so incredibly visionary and vital. It’s not entirely clear to me what he was doing at the time, but how I read it now is, again, with this emphasis on an ongoing project that is a project facing all Americans and very much aimed at and centered on children. That comes up over and over again. The other thing that comes up over and over again, is this kind of rage, this anger, this witness, and so forth, and then there comes this pivot onto something that he calls “love” as the only thing that can save us. And this is not Haight Ashbury, touchy-feely, flower-power love. This is something as complicated as America. It’s something barely attainable, and then it falls away, we mess up.

Blint: It’s not romantic love. Baldwin says, “Love has never been a popular movement and no one has ever really wanted to be free.” Our common understanding of freedom in America is only through its absence, only through its negation—captivity—right? So when he says “free” in that moment, it goes back to the founding: conquest, settlement, and enslavement. But the freedom is to be free from all of the categories that are limiting what we inherit and Baldwin had an expansive proposition about how, again, to fashion oneself down here below: In this place.

Weschler: It’s interesting in this context, you mentioned a second ago Giovanni’s Room, where part of the story is clearly about a deeply closeted white figure, an American in Paris, who gets involved with somebody who is clearly much more at ease with his sexuality. The relationship just curdles and he destroys both himself and his lover through his inability to be free. And he’s not only talking about gayness in that situation.

Blint: It’s all about American innocence. What Baldwin does in that novel that I find so compelling—and to put in a quick little plug here, a panel that Bill T. Jones and I have been working on for the festival called “After Giovanni’s Room: Baldwin and Queer Futurity,” to be held at NYLA—is precisely to this point. David, the lead character in that novel, is just part of what Baldwin calls the “ignorant armies”: these white men who take their position, life, trajectory in the world for granted, in a white patriarchal society. It’s a story of innocence, of the refusal to be sullied by the contradictions of history, which is partly why Giovanni is there as a foil. So he’s both talking about the cowardly nature of Americans who think very little beyond themselves, but more than that, it’s about a commitment to innocence, a commitment to the illusion of “safety.” As he says at the beginning of Nothing Personal, to not stink, to be clean, to not have any taint is what I think he means by “innocence,” and it’s an American innocence. It’s the same thing, to go back to your other point about race, class, and gender, when he calls “civil rights” a decidedly American term. What does that mean: “civil rights”? We have, as he says, the Thirteenth Amendment. He was so prescient, not a prophet so much, but a person who saw the kind of dishonesty, the cowardliness embedded in American vernacular. I say vernacular because it’s the tacit vocabulary of not trying to confront that sedimented history and past—that dense history we all share.

Weschler: What’s amazing to me is that he doesn’t go to Paris and leave America. He discovers his subject in Paris, which is America.

Blint: He discovers it fitfully. What’s interesting to me, and I think it’s really important is that he almost had a nervous breakdown. He landed in Paris with $40 in 1948 and quickly made a lot of friends, but he was gliding: borrowing money for food, going from this hotel to that hotel, surviving on the kindness of strangers. But Lucien Happersberger, his long-time, complicated straight lover, took him to his father’s place in the Swiss Alps. It was there amongst all that whiteness and the music of Bessie Smith and Fats Waller, where he found what he said was “the key to the language” that gave him Go Tell it on the Mountain. We have to be clear about this, Baldwin fled because he was being menaced, but also because he was being menaced internally. He said he had to come to terms with that black pickaninny that Bessie was referencing, that world, to find that language that gave him Go Tell it on the Mountain. He had to confront himself, and love himself, to go back to that, as a way to move forward. That’s always the thing with him: movement. It’s not evolution in the flat way, but a certain radical self-fashioning that comes out in often painful ways. As he often said, he had to “vomit up the anguish.” That’s what he did in the Swiss Alps. In order to get him there, the music helped, but he had to vomit up his own anguish in order to write.

Weschler: One of the things we’re going to be doing by the way, at NYLA, is to display that incredible text that would become The Fire Next Time in its original New Yorker version.

Blint: Oh, talk about that.

Weschler: It’s so amazing how, in those days—we’re in November, 1962, and the New Yorker had no table of contents, or actually they had a completely weird table of contents that didn’t include everything that was in the magazine. [Laughs.] For example, it didn’t include the names of any of the writers.

Blint: What do you mean a table of contents that didn’t include people in the magazine? [Laughs.]

Weschler: The table of contents of the New Yorker in those days read in alphabetical order, “Letter from Rome,” “Poem,” but “Poem” was after “Letter from Rome,” because that was P after L and so forth. And there were a few things that were listed, but the “Letter from a Region in my Mind” was not listed at all.

Blint: No pagination?

Weschler: The pages were out of order, there was no listing in the table of contents, which is typical of the New Yorker, it was like that famous story about the New Yorker, why do you know—

Blint: Ren [Weschler] worked at the New Yorker by the way, for the record.

Weschler: I did for many years. In those days the attitudes were: “We really should do it to help our readers,” “Oh, who cares about them!”. They went dragging, kicking, and screaming into providing any sort of table of contents, and when they did, the one they offered was completely perverse.

In any case, the point was that neither Baldwin nor his piece were listed, that particular table of contents didn’t even list the title which was “Letter from a Region in my Mind.” So, as a reader, you would pick up that issue, and you’re looking through it—and by the way there’s incredible stuff in that issue: there’s a wonderful poem by Auden, there’s a fantastic Saul Steinberg pictorial, there’s Edmund Wilson—and then you’d turn the page and there was this thing called “Letter from a Region in my Mind.” And you might start reading it, it’s three columns. There’s a cartoon and you turn the page and it’s three columns, and then, for the next 44 spreads, 88 pages. there is one column of text—

Blint: I mean slim column.

Weschler: A slim column of text, and five columns of advertising.

Blint: Luxury advertising.

Weschler: And it’s all luxury advertising. All storyboards out of, you know, Madmen— it’s insane. There are cars, drinks, bourbons.

Blint: Furs.

Weschler: It’s Don Draper’s wet dream. And by the way there are no blacks in any of the advertising.

Blint: Well, of course!

Weschler: Although there are black substitutes, so there is a butler—but he’s not black, there is a chauffeur—but he’s not black. All this kind of stuff, and it goes on and on and meanwhile, running through this whole thing, is this: I mean the first thing to say about The Fire Next Time, is that the text itself is on fire! And what I keep wondering is, what did people think as they were reading it? By the way, at the very end, when you turn to the last column, it comes down and it’s the famous ending, “Otherwise we will—

Weschler & Blint: [Chanting in unison] “God gave Noah the rainbow sign, no more water, the fire next time!—James Baldwin.” And on that page, there are a bunch of ads including an ad for jewelry, where the headline is “Chains Abound.”

Blint: You can’t make this shit up.

Weschler: We’re going to make a mural out of the whole article and have it all there on the wall at NYLA—this incredibly incendiary text surrounded by all that superficial, essential luxury.

As the years passed, he was often looked down upon by elements in the black community because he even bothered addressing the white community that way. Or—there were all these ways you could dismiss him, and every one of them was used, and they just didn’t apply. Because the further you get away from that moment, the more vividly clear it becomes that he is the person who was onto it, he understood what was happening.

Blint: With Esquire and the New Yorker, he published in all those places, right? He was a writer for hire, with a certain message, right? It’s interesting to see how it all landed: the editorial manglings, layout manglings—I think only reveal the divide, the chasm, between his message and where America was and is.

Weschler: By the way, where was it that he recorded that conversation with Robert Kennedy?

Blint: Well, Jimmy Baldwin met up with Bobby Kennedy, the attorney general, along with Lorraine Hansberry and a bunch of stars in 1963 to discuss the treatment of blacks, and Baldwin recalled in an interview with Kenneth Clark immediately following something like: “Bobby Kennedy recently made me the soul-stirring promise that one day—within 30 years, if I’m lucky—I can be President too. It never entered this boy’s mind, I suppose—it has not entered the country’s mind yet—that perhaps I wouldn’t want to be.” He called him a boy, the layers of that are really interesting. He goes on to say, “And in any case, what really exercises my mind is not this hypothetical day on which some other Negro ‘first’ will become the first Negro President. What I am really curious about is just what kind of country he will be president of.” So, with the symbolic ascendancy of President Obama in mind, it’s not that he was being uncannily prophetic in recording that conversation, as so many have indicated. Rather he is saying that a black president is not a gatekeeper for the status quo: not the kind of symbolic figurehead for an America that will proceed uninterrupted.

Weschler: Where he’s prophetic is in understanding, parenthetically, all the way across the board, all the black mayors, the black governors, the black, you know, who are put there precisely to—

Blint: It’s incredible that it’s still going on. This happens in popular culture, too, and he talks about this in The Devil Finds Work: what happened, for instance, to Sydney Poitier in In The Heat of the Night, his incredible analysis of how our cultural predilections, our cultural arrangements, require the black lieutenant, a black sheriff. Not the sheriff so much, but, you know, the kind of black, special individual: lonely, isolated, that supposedly shows just how far we’ve come.

Weschler: By the way, do that sentence again and put Obama in your mind as you say it: The black, lonely individual that shows how far we’ve come. I mean Obama is just, he is so alone.

Blint: What do you mean he’s alone? Talk to me more about that. In a Baldwinian way.

Weschler: I guess I was coming at it from out of that Robert Kennedy story, which is that—well there is a different story that I could tell you. In a different part of my life, I was running the Chicago Humanities Festival and I got to know many of the people who vetted Obama. They’re good people, they’re sweet—they’re philanthropists and so forth, but they’re basically right-leaning democrats, Democratic Leadership Council types. They were able to tell everybody else, “Don’t worry, this guy will not shake things up.” They had this fantasy that he would be something, but that he wouldn’t fundamentally ever—

Blint: They were saying he’s middle of road…?

Weschler: He was vetted, which to my mind, is fairly tragic. By the way, we are calling the thing at NYLA, “James Baldwin, This Time!” the point being to ask what he would say about all this. That’s what I want to channel by reading him, by having other people talk about him, and having people talk about the politics.

Blint: Let me interrupt you for a second. I organized a conference in 2011 called “James Baldwin’s Global Imagination,” and at the conference, Kendall Thomas—Nash Professor of Law at Columbia Law School, wonderful writer, thinker—recoiled when this came up, “What would Baldwin say about?” That happens all the time and I chafe against it, too. Baldwin did his work: it’s not up to him. It’s up to us. We can use him, but what are we going to say?”

Weschler: Okay, that’s good.

Blint: There’s something nostalgic about that wish, “What would Baldwin say now?” We have the duty, the responsibility, to gather the fragmented pieces of our history yes, precisely, in this time, and do that for ourselves. So when you ask me to rephrase that question, “Put Obama in it,” I think that’s what I’m talking about. Periodizing it in our own language. We have this history but it’s not about asking Baldwin to speak for us now. We have some work to do.

Weschler: I think that’s true, I also think, though, that it’s true that writers read us. And what does it feel like to be read by Baldwin? That’s what I’m talking about.

Blint: It’s definitely something. We don’t even have to go that far back. In 1982, Baldwin produced, with Pat Harley and Dick Fontaine, a film called, I Heard it through the Grape Vine. Have you seen it?

Weschler: No.

Blint: It’s Baldwin returning to sites of the Civil Rights struggle in the American South. One city which is Southern, in a particular kind of way, is Newark, NJ.[Laughs.]

Weschler: Where he had horrendous—was it Trenton where he had that horrendous incident just before he fled America?

Blint: Exactly. In the film he goes back to all these places he visited after he came back in ’57 and the film begins with a question. He says: “Malcolm, Medgar, Martin, dead, but what about those unknown, invisible people who did not die, but whose lives were smashed on freedom road?” So in response to our lazy penchant to celebrate, you know, Malcolm and Martin, Martin and Malcolm, as these great figures, he’s asking, “What about that body of people, who were here, who are still here, and whose lives are continually smashed?” That’s the question he poses at the beginning of the documentary film, it goes from Atlanta to DC, to New Orleans, Florida, Newark—riveting, compelling—and the diagnosis and the prognosis are the same: We haven’t gotten very far. In fact, things are quite worse. Baldwin was talking in 1963 about gentrification, in Take this Hammer, the film that came out of him touring urban renewal, how people were being really razed up from San Francisco proper to Oakland and other areas that are not really quite as nice. Oakland is nice, I love Oakland. [Laughs.] But what I’m suggesting is that you see that in San Francisco now, where the only folks you see in the streets are folks who are not doing well in this world. And he does that in ’63, and in ’82 he’s effectively doing the same thing. It’s the same film but it comes off as much more of an indictment of American society so I think he’s given us a lot about our present moment, our present crisis.

Weschler: In terms of the present crisis, I can’t believe it, but here we are doing voter disenfranchisement all over again and the explosion over the past few decades in the prison population, the New Jim Crow. One interesting thing that may be one of the few things Baldwin actually got wrong is that at one point, when there were 300,000 people in prison, he said, somewhere, I can’t remember where, “They can’t imprison everybody.” Turns out they could.

Blint: It’s not like he got it wrong, exactly, people say that kind of thing all the time, but what he was imagining was that people would rise up and what he didn’t account for was the kind of sedative that has us all in a kind of political slumber. But he also didn’t account for neo-liberalism, and privatization. And how could he?

Weschler: There are almost 10 times as many prisoners today as when he said that.

Blint: Absolutely, and 300,000 was beyond the pale!

Weschler: It was beyond belief. How many more can there be? And yet—

Blint: He didn’t account for the Southern strategy—

Weschler: The War on Drugs.

Weschler: Law and Order.

Blint: That bullshit idea of the rule of law that is really about criminalizing black people. He didn’t account for that, but also, more importantly, his sense of what people would do, of what they could stand. He referred to the Civil Rights Movement as the latest slave rebellion which is true and so not true, because there are so many people who were not on board with that, but the language was one of polemic and slightly propagandistic as a way to kind of get people up, that’s what he was doing in those speeches. So I give Baldwin some latitude.

Weschler: Yeah, I’m not saying he was wrong. Phrased differently, I want to take Baldwin’s passion and address it to some of these things today, and I want to read that stuff through him reading me, that’s what I mean.

Blint: Absolutely. I think that’s the way we have to do it.

Weschler: When you’re talking to your students today at Columbia, have they encountered Baldwin in high school somewhere? Or they haven’t even done that?

Blint: I teach in the Masters program so some people have, depending on their specialties. A lot haven’t. If they have, it’s been cursory.

Weschler: And so you say, “Okay we’re going to read this,” and what kind of response do you get?

Blint: They love it. But a lot of them want to encounter Baldwin as someone to be critiqued. They find his morality, his propositions utopic, which says a lot about our culture, the millennials. And they read him from a contemporary frame, not all of them—a lot of them love him and see themselves in his work. I’ve been stunned actually by the penchant for graduate students to—I think everyone is up for critique, right? And there’s little humility, at that level, right? I’m not talking about high school students or undergraduates. But I think it happens with undergraduates, for sure. It happened at Hunter College where I taught undergraduates and at NYU. There’s no history, there’s no context for him so what has often been, not painful, but difficult and challenging, pedagogically, is to have them shift from thinking in the present to listening to what he was saying at that time, at a very politically, socially urgent moment. They try to take him out of context all the time, to take him out of history and look at him saying, “Well this doesn’t make any sense. That’s too fanciful. Love? What’s that?” You know? And I’m a different kind of person. I know the full history and the history of the country in that way and the different Baldwins that turn up at different times. From his first published essay in ’49, “Everybody’s Protest Novel,” to his ’85 essay for Playboy, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood.” There’s no hagiography here, no mere reverence. But the kind of impulse to critique, the impulse to suggest that he was hanging his hat too high is dispiriting for me.

Weschler: There’s a way in which critique disguises itself, or tells a story to itself that it’s being political, but in fact is often profoundly anti-political.

Blint: It’s anti-intellectual. It aims to shut something down.

Weschler: It’s isolating.

Blint: Baldwin is available for individual analysis and interpretation, but I think it’s important to understand him as being from a particular historical period, doing a particular kind of work. He was asked by some reporter I think before the premiere of Blues For Mr. Charlie, “Mr. Baldwin, do you think you’ll ever write anything that doesn’t have a message?” and Baldwin laughed condescendingly. He laughed and said, “No writer who has ever lived has ever written a line without a message. What you’re asking me, I think, is to what extent do I intend to become a polemicist or propagandist?” And he said he couldn’t answer that. The anti-intellectual impulse, with regard to Jimmy, always took the form of: Can you stop? Just stop. We heard you the first time. Sit down, will you please.

Weschler: Again? Again?

Blint: The same message, Jimmy? Really? Come on! It’s just people not really ready for transformation. And that’s his proposition. The overhaul of our danger, of our crisis, that’s how he always characterized it. He’s not wrong.

Weschler: Let’s assume there are some people reading this who’ve never read any Baldwin, what should they start with?

Blint: Oh my god. I get this question all the time. It depends on who you are and what you like. If I had to do it again, I would start with [pause] there’s so many, my god. I would start with his last essay, “Freaks and the American Ideal of Manhood.”

Weschler: How so?

Blint: It’s a comment on American masculinity. Its dimensionality, its mystery, its mythology, its amazing blind spots.

Weschler: This is the piece that he did for Playboy?

Blint: Yes. It was later published in The Price of the Ticket as “Here Be Dragons” and it does so much work. It’s not simply about homosexuality, or anything like that. It really gets to the American ideal of manhood and what it does to incipient masculinity, meaning how do you fashion yourself as a white man in the world. It does away with so much, so effectively, so precisely, so beautifully. I love it, I teach it all the time. I write about it. It’s my own personal favorite. But what should someone start with? That’s a really personal question. If Beale Street Could Talk, for instance, that’s ’74, right after all the assassinations, and people call it his bitter novel, about folks in jail. It’s his incarceration novel—a love story. One could start there. One could easily start with Go Tell it. One can easily start with a lovely collection of short stories called Going to Meet the Men and start with the closing story, the title story which, again, is about how incredibly masculinity and desire are tied up with race. Also, the novels are incredible. Another Country is great.

Weschler: Giovanni’s Room.

Blint: Giovanni’s Room is incredible and is a lesson in what we’re talking about: not racelessness, that’s not what we’re saying at all. As I said, there are no black characters in that book and that’s a lesson, for me at least, about Baldwin’s range and command. He said he wanted to write something about a certain kind of American man that he doesn’t know very much about and that kind of myopia, that kind of indulgence. How a person can be in Paris just fucking himself through life and trying to avoid the fact that he’s a homosexual? A lot of us can’t move in the world in that way, so I found that incredibly successful, but it depends on who you are.

Weschler: I would add to that obviously Fire Next Time.

Blint: Of course. The last thing I want to say, though, is that we ignore Baldwin at our peril. We ignore him at our serious peril. Folks have no idea of the forces organized and marshaled against our own thriving, and marshaled for our own destruction. I’m not being hyperbolic here. I think we’re in real trouble and I think people really have to wrestle with, grapple with, think through, and analyze, where we have landed, and what’s coming. The children are really crucial here, it’s not anything to take lightly. Folks think that there is always time, and maybe we should leave off with what he said in his essay “Faulkner and De-Segregation”: “The challenge is in the moment; the time is always now.” It’s an old Baldwin maxim, very familiar. I think people need to understand that: that the challenge is always now. People seem to think we can keep putting it off, putting it off, and putting it off, but the work that is before us has to be continued with his call. James Baldwin, this really is our time. I want to stress in this conversation and throughout The Year of James Baldwin, we absolutely cannot keep deferring, delaying the work before us.

Weschler: Amen.