Tomaselli’s Times

Virginia Quarterly Review | Friday, May 30, 2014

The piece that follows is an abridged version of the title essay in the recent book documenting this body of work of Tomaselli's, The Times, just out from Prestel.

Fred Tomaselli has been busy slaughtering mosquitoes this past summer, or so I am given to understand one afternoon when I visit with him in the spacious walk-up studio he occupies in a converted small-industrial building in the Bushwick section of Brooklyn. I have come with the intention of talking about an entirely different recent passion of his: the vivifying, that is, of dead newsprint.

But first back to the mosquitoes, because in fact he is killing, collecting, and cataloguing the insects in question. Every morning he inventories a fresh batch from the bowels of the high-tech German mosquito-catching machine he procured from an entomology mail-order outfit and methodically lays out the night’s harvest gridwise across a paper towel and photographs the results. “You can toggle through them,” he exults, full of boyish nerd marvel, riffling through the photos. “Look, July 18, just a few days ago—122 mosquitoes! I admit it, I’m a complete autistic taxonomist when it comes to trying to figure out and understand the shape of the world. But in addition I just love gloating over the corpses each morning—I love being able to reverse the bloodfest.”

What I love about the story is its dailiness (“Oh yeah,” Tomaselli agrees, fanning out the prints, “this is like my diary.”) and its ritualized nature (“Absolutely. I am very much about rituals; it’s probably the lapsed Catholic in me.”). Both are qualities that go all the way back to the mornings of his very first job as a news-paper-boy, rubber-banding the papers and setting off on his bicycle to toss them across the tract front lawns of his hometown subdivision in Santa Ana, California, the rising sun casting its long shadows in the very lee of Disneyland. “No doubt about it,” Tomaselli avers, “I’m a news junkie to this day—I just really get a kick out of watching the history of the world unfold on a daily basis.”

Junkie, perhaps, being the operative word there, for the other thing Tomaselli famously was in those halcyon days of his Southern California youth was an avid enthusiast of variously mind-altering drugs and plant extracts. Nothing too over the top, but he was hardly a mere piker, either, and the experiments left their lasting perceptual residue: a way of seeing the world in the fullness of its swirling dips and whorls. Indeed, the suburban-bred Tomaselli suggests that the drugs are what first turned him on to nature. By the time he was building toward his bachelor’s degree in painting and drawing at nearby California State University, Fullerton, he was spending a good deal of the rest of his time tending a small-scale backyard marijuana operation. “In order to hide my crop,” he confesses, “I built up this border of tomato and other vine plants all around the edges, and gradually those borders became even more interesting to me than the stuff they were intended to hide.” He doesn’t know about other people, Tomaselli likes to say, but for him marijuana proved a gateway into gardening.

And that love of gardening, in turn, prefigured a love of birding and birding books. “Birding actually started for me a bit later,” he explains, “one day when I went birding with my brother. I mean, before that, birds were just like, what, dirt in the sky; I had never paid much attention to them. But I had the binoculars and all of a sudden I see this little thing and I focus in on it—it’s this brilliant little orange, yellow, and black creature clinging to a branch—and I look it up in the book and go, ‘Western tanager!’ And I realized that I was understanding something about the environment that I had never understood before. It was really fascinating to me, this idea of a parallel reality that really only needed to be unlocked with a certain kind of knowledge, a certain kind of information, and a certain kind of enhanced optics—all of which seemed especially relevant to me from a painterly point of view. All us artists really are just trying to wipe everyone’s eyes clean and clear, our own included. I think a lot of artists are basically saying to their viewers, ‘Pay attention to this, I find this interesting.’ ”

Attend. Only attend.

“Yeah, attend to this idea, attend to this thing, attend to this vision. But I think you’re right: Gardening, too, is an apt metaphor for making art, insofar as you start with this sort of chaos of the vines and weeds and whatnot, and you take your sensibility and you cultivate this chaos into what you want it to be. You weed it and you add things and subtract things. And slowly you grow it out.”

So it’s not just “Only attend”; it’s also “Only tend.”

“There you go. You attend by tending. And so both of these hobbies of mine—these useless hobbies that have nothing to do with art—actually had everything to do with informing my sensibility.”

Might the same be true of another of his loves, fly-fishing?

“The thing I love about fly-fishing is how you have to understand the entire stream ecology to catch fish. Not only do you have to understand what the fish are eating, you have to understand stream entomology so as to be able to mimic the insect—how it lands on the water, how it floats along the water. You basically have to become one with that whole entomology-predator interface. And it’s all very specific to where you are—the flows and eddies and microclimates and everything else. So it’s an interesting way of unlocking the totality of a particular ecosystem.”

Which again has a lot to do with his painting, doesn’t it?

“I think so, yeah: the focus on being there in the moment.”

And then, as well, there’s the whole beauty of the activity itself, the arcs and swells of the unfurling line. Does he think about that?

“Well, they do call us anglers, you know? Because we are creating angles in the air. Though of course it’s more than mere angles, because what’s really fascinating about fishing, and specifically fly casting, is that you’re actually drawing a big, perfect line in the air and your whole body has to become part of that line: It’s all about loading it with power and then releasing power. And you have to feel it in your body. Furthermore, it’s one of those things that has to become unconscious in order to work. When you’re thinking about it, you’re making terrible lines. And in a funny way, I would say that when it’s all working for me here in the studio, when my lines are singing, it’s the same thing: I’m not really thinking. My hand is doing all the thinking at a certain point. That’s taken me awhile to get to, as an overly cerebral artist who’s constantly freaking out about what art is and what good is it for and all the other questions. But increasingly that’s been the way I try to approach things.”

In 1985, on the eve of turning thirty, Tomaselli left Los Angeles for New York—no big decision, he says, it was just time for a change of scenery—alighting in a little detached house in Williamsburg in whose backyard he was able to resume his gardening and where he began embedding psychotropic drugs (the actual pills themselves, arrayed in lines) in gleaming, reliquary-like votive panels. “I liked playing at rearranging the use value of the objects in those works,” Tomaselli explains. “Encapsulated in tamper-proof resin, those chemical cocktails lost their street price (they’d been ruined as pills) but acquired a different sort of artistic value, whatever that might be. In addition, they could no longer reach the brain through the mouth, stomach, and bloodstream and had to take a different route to altering perception. In my work, they traveled to the brain through the eyes.”

And presently the other way around. The psychedelic visions of his youth poured out of his brain, projected as if out of those very same eyes onto ever more complex and polymorphous images of bodies, birds, and eventually fish, shingled together out of thousands of vividly delirious details culled from all manner of anatomy texts, field guides, and road atlases, and sometimes including actual mushrooms, insects, or pressed flowers: all the mind-blowing imagery that has become Tomaselli’s calling card.

For more on all of that, there are texts and catalogues. For our purposes, though, one salient fact about Tomaselli’s transfer to New York is that it afforded him exposure to a far greater variety of art exhibitions, none perhaps as moving and seminal for him at that point in his career as the big 1993 Joan Miró retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art—in particular, a little jewel box of a room containing canvases from the Catalan master’s Constellations series.

What, I now ask, had so struck him about those paintings?

“Outside of their cosmic beauty—these biomorphic spangles of different colors arranged somewhat like stars on paper—the thing about them that really bowled me over was the way he had been doing them at the height of World War II, while France and Europe were either occupied or burning and he himself was actively having to move around Europe, trying to stay away from the Nazis.”

Were they big images?

“Not too big, no. They’re sort of portable, as they had to be. They read as incredibly cosmic, serene, almost defiantly otherworldly, and yet they struck me as being quietly political insofar as Europe was burning, one of the worst periods of human history was unfolding, and here this guy was making these things that insisted on some cosmically beautiful connection to the heavens. They seemed to be advocating for a certain kind of humanity and humane culture at the very moment that that culture was being destroyed, those people were being destroyed. Such that the mere fact that they existed was profoundly political.”

There’s that lovely, haunting late poem by W. H. Auden called “Archaeology,” to which he appends a coda:

From Archaeology

one moral, at least, may be drawn,

to wit, that all

our school text-books lie.

What they call History

is nothing to vaunt of,

being made, as it is,

by the criminal in us:

goodness is timeless.

“I think he’s onto something there,” says Tomaselli.

Everything else is just peripheral. Or phrased differently, perhaps: Poetry is news that stays news.

“That’s beautiful, too. Who said that?”

Ezra Pound. But coming back to the subject at hand, didn’t Tomaselli’s response to the Miró show in some ways prefigure his own subsequent New York Times series, in the sense of its trying, if not to escape the everyday chatter of the news, somehow to transcend it, to locate something more cosmic or infinite or . . .

“I don’t know if I feel comfortable talking about myself in that company. I am happy to talk about Miró, who was transcendent.”

All right, but couldn’t it be said that somebody who felt that way about Miró might well go on to create some of the work we are talking about now?

“Well, perhaps.”

So how had this New York Times series come into being?

“Well, this was deep into the second Bush administration, the miserable fiasco of the Iraq War, and, despite that, his reelection, and I seemed to be yelling at the paper almost every morning—those were immensely frustrating and exasperating years to be a news junkie. And presently the yelling escalated to sometimes scrawling all over the paper—‘Fucking asshole’ or ‘You bastards!’ or whatever—and Laura, my wife, would go, ‘Oh, you’re wrecking my New York Times.’ So I was already editorializing and graffitiing all over the paper anyway, and I decided to go with it…I just started drawing on it.”

What else was he doing in those days, workwise?

Guilty, 2005. Perforated archival ink-jet print, 13 x 13". (Courtesy of the artist and James Cohan Gallery, New York / Shanghai.)

“I was doing my paintings. Probably the giant megabirds that were based on Arcimboldo. A few years earlier I had done a work that referenced Masaccio’s expulsion of Adam and Eve.”

The expulsion from paradise.

“From paradise, yeah, which is one of our fundamental stories about our struggles around utopianism, culturally. And that had always struck me as an interesting allegory to bring into my own work, which kind of comes out of the rubble of utopian thinking—all that sixties transcendentalism and whatnot, with me inheriting that legacy as it all crashed and burned. In a funny way, that work seemed emblematic of a certain feeling permeating the culture—that we’d become separated from this lost paradise. So anyway, I had done this work based on Masaccio’s Expulsion from the Garden of Eden, and then one morning I saw this one particular photograph staring up at me from the front page.”

The image that he used for Guilty (Wednesday, March 16, 2005).

“Bernie Ebbers, the just-convicted WorldCom chairman, clutching the hand of his wife as he was being expelled from the Eden of finance by the camera-wielding angels of the paparazzi. And all that day, I kept returning to the image; I actually took the paper with me to the studio and just kept looking at it. Surely part of the reason I couldn’t get it out of my head was the historical art references that it kept conjuring up, specifically to Masaccio. At the same time, I was really compelled by the clutching of the hands and the humanity that showed. Despite his monstrous crimes, this guy was still a human being and he had a wife who loved him—or at least pretended to love him in public. And there was something touching about that.”

Especially the hands.

“Indeed, I did tend to focus on the hands.”

Touching the way images of hands so readily reach out and touch us.

“The fact that they were a couple clutching each other seemed very much like the way Adam is holding Eve in the Masaccio work. Also the look of horror on his face like his whole world is falling apart, that look of being utterly stunned by the verdict. My brain was becoming discombobulated the longer I looked at the image, and I started drawing over it. At first, I maybe just wanted to mask this guy; maybe I wanted to turn him into a bigger, more horrific creature. But as time went by, I realized that I didn’t want just to vilify him. I also wanted to focus on that luminosity of human connection. I wanted to take on the photograph with all of its complexity.”

Now, at that point, was he already imagining, Hey, this is something really cool; I can start doing this every day?

“No, I just did it.”

Did he go out and buy several copies of the newspaper, or make copies and work on them over and over again?

“No, I did it on the original.”

And is that always the rule, that he does it on the original? Or does that vary?

“Eventually, methodologies came up that are more in place from work to work. But at that point, I didn’t know what I was doing. It was not even intended to be art; it was just something that I was investigating because I felt like I needed to.

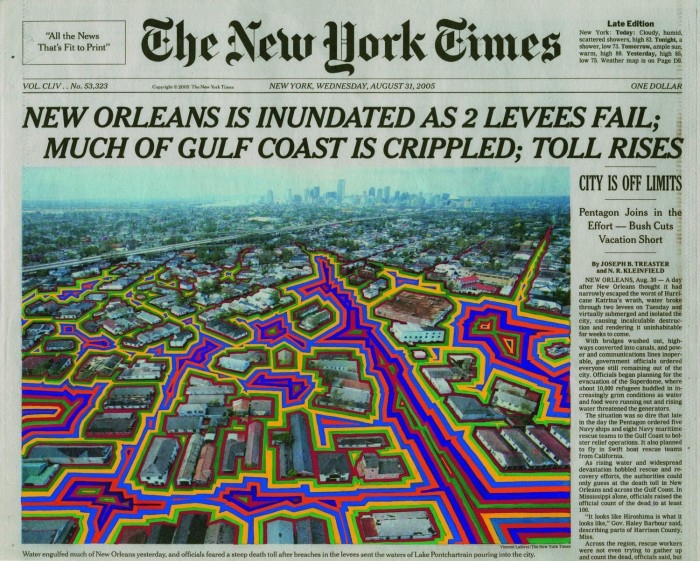

“So I made that thing, and I didn’t do anything else like it for a while. And then New Orleans happened.”

Hurricane Katrina and its aftermath (Aug. 31, 2005 #3). His responses there, though, were quite different: far more geometric, formal, if anything drawing on Kenneth Noland or Piet Mondrian.

Aug. 31, 2005 #3, 2009. Gouache and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 15 x 17-1/2". (Private collection, New York.)

“Every work I do, I am trying to address the specific formal or ideological or content issues of the image in question. The work has to meet the image on its own terms.”

Indeed, one of the very next ones—bombing victims laid out in a Baghdad hospital (Sep. 15, 2005 #2)—was again entirely different in tone: more ornate, “oriental” in its overlay of looping vines and collaged flowers.

“Yeah, that was such a heartbreaking image. I found myself wanting to honor the victims in some way, and presently those organic arabesques began to assert themselves—an echo, perhaps, of Arabic calligraphy or all that amazing tilework. And then, too, I used to get a lot of juice out of looking at Mughal miniatures, like the show at the Metropolitan Museum of Art awhile back where you even got to peer into them with these magnifying glasses they provided: the incredible detail, sometimes applied with brushes consisting of a single hair.”

Speaking of which, what was the medium that came to predominate this series?

Sep. 15, 2005 #2, 2010. Gouache, collage, and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 8-1/4 x 10-1/2". (Private collection, Houston, Texas.)

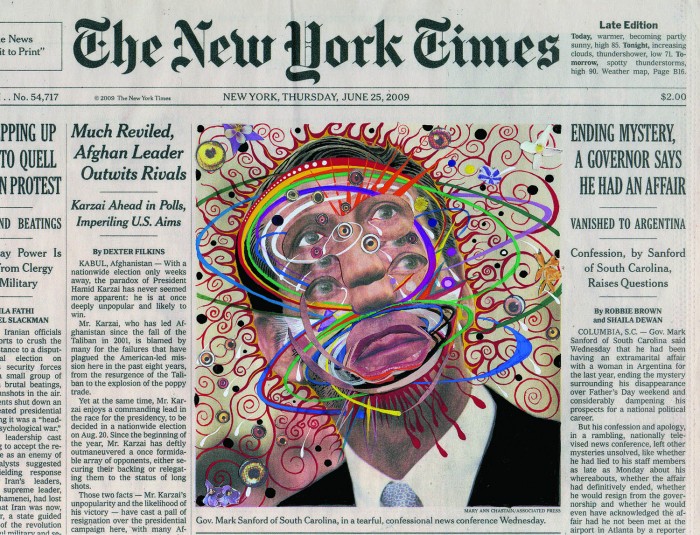

June 25, 2009, 2010. Gouache, collage, and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 8-1/4 x 10-1/2". (Weatherspoon Art Museum, University of North Carolina, Greensboro.)

“Well, collage, as with some of my bigger paintings. But then mainly gouache, which is a sort of opaque watercolor. It comes in tubes, and the cool thing about gouache is that you can paint over it—one color on top of another—without bleeding through as it would in ordinary watercolor; but you can also thin the stuff so it becomes more translucent. And I use super-detail-oriented, tiny fine-point brushes—maybe not a single hair but sometimes not much more.

“As time went on, I’d scan the front page of the paper—I now have an archive of every single front page going all the way back to 2005. I’d scan the front page and then print digital facsimiles on archival watercolor paper, which I can then cut up or reprint as many times as I want—that allows me a lot of freedom. On the other hand, I am not unaware that the very sorts of digital tools I’ve taken to deploying are responsible to a considerable degree for the distress increasingly afflicting the print media I so love. Such technological advances constitute a decidedly mixed blessing.”

I comment that, like him with his mosquitoes, I evince a certain taxonomic streak myself: I’ve noticed how one can trace certain distinct series across the breadth of his whole New York Times project, beginning, for starters, with compounding variations on those first three pieces. Thus, for example, the Expulsion from Paradise, the Perp Walk of the Shamed, clearly became an ongoing motif.

“Indeed. For one thing, there’s the Horror of the Bernies, since a few years later we got the other one: Madoff [Dec. 18, 2008]. And there’s South Carolina governor Mark Sanford, who had to resign when he was caught having absconded to Argentina with his mistress when he’d claimed to have been out hiking the Appalachian Trail [June 25, 2009]. He had such a long face to begin with, and eventually I just decided to keep stretching it. I was having fun at his expense, too. Often, though, I’m just goofing around and playing with stuff until I get what I didn’t know I wanted. It’s through experimenting with media and just playing around that I end up finding my way. It’s like: ‘Oh, wow, I had no idea this is the thing I wanted to make, this is the thing I wanted to see.’ ”

But let’s unpack that sentence: I had no idea. There was no ideation. Which is really saying something for someone as cerebral as Tomaselli.

“Look, if there’s one major change in my work from the time I started in the eighties to what I’m doing now, it’s that I’m increasingly less sure of what I’m doing. And less cerebral, and there’s less and less predetermination in the work. And that, in a funny way, keeps it interesting. When my work was more predetermined, that was fine for getting me out of the bind I was in, right? But now the not-knowing is the really exciting adventure in the studio. And it’s by making that I find out how to know the thing that I want to see.”

About those dwellings “vacancied long ago,” the archaeologist …

has not much

to say that he can prove:

the lucky man!

Knowledge may have its purposes,

but guessing is always

more fun than knowing.

“Who said that?”

Auden. Late Auden. Same poem.

“I have to go back to Auden. Who in turn puts me in mind of Isherwood, and it’s certainly the case that many of these pieces owe a lot to the German Expressionists, to George Grosz and some of his Weimar colleagues and the way they treated their monstrous villains by way of exquisite grotesqueries. I do feel a kinship with the German Expressionists in that regard.”

Definitely. John Heartfield, too, comes to mind, as does Hannah Höch.

“Both of them sublime collagists who, yes, both often worked off newsprint images.”

In fact, another version of the Perp Walk of the Shamed feels very like a Heartfield: Tom DeLay, having to resign as majority leader of the US House of Representatives after being indicted for election-law violations in Texas (Sep. 29, 2005).

“Yeah, I was able to turn him into an evangelical snake handler who was blowing his top. Part of that was suggested by all those microphones with their coiling electric cords snaking up to the podium. I was responding to that by inserting serpents, which in turn got me thinking about snake handlers and the hysteria of American Protestantism that he was selling to the rest of us. I don’t want to say that he was just a guy selling snake oil because that would be too cute—except I guess I just said it.”

Another in the series of the Shamed, the Expelled, and in some ways the most wrenching, is the one of Raj Rajaratnam, the convicted hedge-fund manager (May 12, 2011). Not so funny.

“He is being turned into a skeletal creature. He’s virtually being vaporized by all this media attention, the rabid, carnivorous gaze of the paparazzi. So it’s about seeing and not seeing, being seen and not being seen.”

The Perp Walk of the Shamed proves only one of the leitmotifs running through Tomaselli’s series. Another, which likewise surfaced right from the beginning, is that tendency for formal geometries. Thus, post-earthquake Haiti in ruins (Jan. 14, 2010and Jan. 16, 2010); the bombing attack on Shiite demonstrators in Pakistan (Sep. 4, 2010); the fate of the Guantánamo prisoners (Apr. 25, 2011), in which the geometry becomes almost web-like in its constriction; and Syria (July 25, 2012), where evidence of the war’s having reached Aleppo is veritably tessellated over with ornate tilework (note the homonymic pun with the entirely coincidental report beneath the image on a “Mogul’s Latest Foray”).

“With many of those, yes, I am struggling to find a way to channel my horror or grief, and in particular not to play with or play off images of death: to give the dead their due—their privacy, as it were, while still acknowledging the scale of the tragedy of their passing.”

It seems to me, however, that he addresses that same concern in a variety of ways besides the geometric. Indeed, I have noticed another subgroup of pieces we might label, for purposes of shorthand, Sorrows and Victims. For starters, as mentioned earlier, there is that version of the Baghdad hospital with its arabesque of vines and flowers (Sep. 15, 2005 #2). But then as well there is the startling image of an American soldier diving for cover during an ambush in Afghanistan (Apr. 20, 2009), and, soon after, the haunting apparition of two American soldiers bejeweled in flowers as they amble peaceably across a poppy field just moments before another ambush (Apr. 29, 2009).

“Across this body of work,” Tomaselli tells me, “I’ve often thought about Susan Sontag’s admonition, in her Regarding the Pain of Others, against aestheticizing suffering. It’s an ongoing quandary.”

What about Dec. 27, 2012, in which it seems he’s actually injected a note of moral quandary into the image that he started from?

“‘Signs of Changes Taking Hold in Electronics Factories in China.’ Yeah, it’s an assembly line of women working in an electronics plant in China. But they were dressed in white smocks that very much reminded me of doctors’ outfits. And I started thinking about the ramifications of globalization in general. This idea of cheap outsourced labor coupled with the fact of endless war to achieve resource domination. I guess I wanted to conflate the two: Instead of them making iPhones or whatever they were doing in the original photograph, I thought I’d have them operating on this pile of victims of various geopolitical conflicts. Those are actually Iraqi war victims. Not that China has much to do with Iraq, but they all seem to be symptomatic of a global corporate takeover of the world, and the wider idea of cheap labor and endless warfare as the props undergirding other people’s—which is to say our own—material prosperity. The idea of the grime and the suffering that brings us these beautiful streamlined products.”

Apr. 29, 2009, 2010. Gouache, collage, and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 8-1/4 x 10". (Collection of Miss T. Moore, Palm Beach, Glorida.)

Such as the very one we’re using to record this conversation.

“Exactly. I wanted to explore some of those uncomfortable juxtapositions.”

The director Steve McQueen mined similar terrain in his 2007 short Gravesend, which follows the manufacture of coltan from the incredibly bleak and gritty open mines of equatorial Africa through the gleaming robotic labs where the object of those grim miners’ desperate labors gets refined into all manner of techno-baubles.

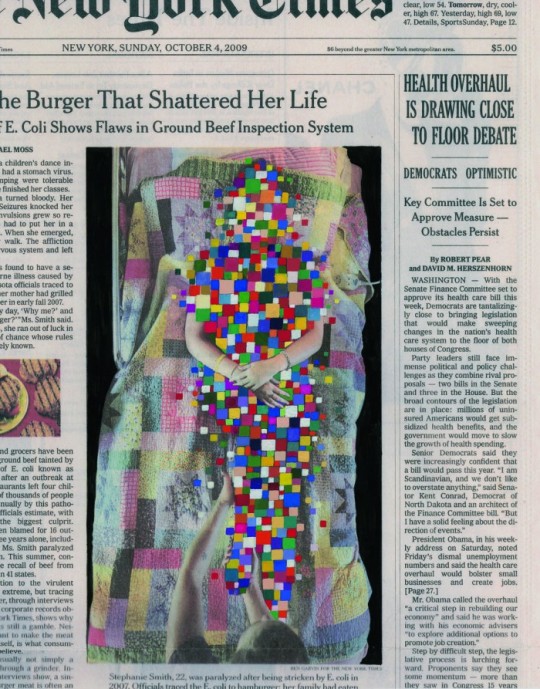

In an entirely different register, while still in the same general terrain of Victims and Sorrows, comes “The Burger That Shattered Her Life” (Oct. 4, 2009).

“That was a funny albeit quite arresting headline, though the story underlying it was anything but funny. And I kind of like how I resolved the voyeuristic dilemma there: It’s almost like the victim is becoming a Klimt or something. There’s something jewellike, a transformational thing that’s occurring. I think it’s actually one of the prettier ones I’ve made. And I do feel that by occluding her face in that percolation of color, by not having the eyes—her eyes, her face—I’ve removed that element of voyeurism, of being entertained by the suffering of others. Which I really try to avoid, except when they deserve it.”

A comment that brings me to an entirely separate category, at least in terms of my own taxonomy of the Universum Tomasellianum, which is to say the Takedown of Those Who Have It Coming (even if, as it happens, they may not yet have fallen from grace). The fierce militancy of Iranian president Mahmoud Ahmadinejad’s second inauguration is mock-smothered in garland upon garland of flowers (Aug. 6, 2009); elsewehere, newly elected New Jersey governor Chris Christie appears as a bouncing clown, vaguely reminiscent of Thomas Nast’s Boss Tweed (Nov. 4, 2009); and Arizona senator Jon Kyl veritably pullulates with the righteousness of his fist-pounding rage at the prospect of an arms-control treaty with Russia (Dec. 22, 2010).

Dec. 27, 2012, 2013. Gouache, collage, and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 10-3/4 x 12". (Collection of Steve Tisch, New York.)

Oct. 18, 2011, 2012. Collage and archival ink-jet print on watercolor paper, 11 x 14". (Private collection, Aspen, Colorado.)

Tomaselli reserves some of his greatest multicolored enthusiasm for the ongoing spirit of rebellion. Wisps of the sixties come wafting back in his own time, with the young rising up in Britain (Nov. 11, 2010), in Italy (Dec. 1, 2010), in Britain again (Aug. 10, 2011), and finally in America (Oct. 18, 2011), where the artist captures the spirit of the entire Occupy Wall Street movement by way of the determined exasperation of a solitary young woman holding up a sign that simply proclaims, i am very upset—a message that in Tomaselli’s hands just keeps ramifying and ramifying high up into the sky.

In other words, these are the times of one determined New Yorker, an act of witness, a Book of Days across an age of tumultuous transition, a mad cacophonous era headed hell-bent and at full throttle who knows where. That, incidentally, may be one of the reasons that Tomaselli has limited himself to the top of the fold of the front page of his hometown paper: to peg this project specifically as a chronicle of these here times.

This body of work has hardly been Tomaselli’s main focus over the last decade, a period that has proven exceptionally productive in all sorts of other ways. He talks about the Times pieces as capriccetti—brief, larkish, improvisational excursions from other more ambitious, focused, and often months-long engagements. He undertakes them in the spirit of play, but serious play.

“Each morning,” he concludes, “I wake up, plod out to the kitchen, grab my cup of coffee, spread open the paper, and tend to the garden of my times.”