The record smashing Hockney Auction

The Atlantic | Sunday, Nov 11, 2018

On a snowy evening in New York City, David Hockney’s 1972 painting Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures) sold at auction for a jaw-dropping $90.3 million, shattering the previous world record for a work sold at auction by a living artist—Jeff Koons’s Balloon Dog, which went for $58.4 million back in 2013. It also far exceeded the estimated sale price of $80 million, which itself would have been a record. What do these kinds of prices say about the state of the art world, and of the world in general?

The Hockney painting is an unquestionable and probably timeless masterpiece (perhaps unlike the previous record holder). One can make an argument that it is one of the two or three most crucial canvases of the ever-youthful, now-81-year-old British master’s career. As the people at Christie’s (the ones putting forward the $80 million figure) are delighted to point out, the work marks the only time Hockney combined two of his most popular subjects: a swimming pool and a double portrait.

Swimming pools had transfixed Hockney since he first arrived (from cold, gray northern England) in sunny Los Angeles in 1964. The young artist began seeing, as if for the first time, the artistic potential in things that everyone else in the southland had been taking for granted. The way the turquoise water moved and gleamed and eddied was manifestly beautiful, but it was also, for Hockney, something altogether more fascinating. What really interested him was the way light scattered across the surface of the water, a wide, two-dimensional skin that could nevertheless be seen through—not unlike a painted image splayed across the canvas itself.

Meanwhile, for all its colorful seductions, Portrait of the Artist served as the culmination of a half-decade-long series of neorealist double portraits—studies of pairs of friends and, at the same time, investigations of the relationships between those friends. And in this instance, that investigation was especially fraught. This painting is in fact the second version (he’d abandoned and destroyed the first version) of an image that Hockney had, by that point in 1972, been working on for well over a year—a year that saw the traumatic breakup of his five-year relationship with the image’s principal subject, Peter Schlesinger, in that pink jacket, arguably the love of his life.

What are we to make of the swimmer coursing underwater as he approaches the pool’s rim at Schlesinger’s feet? Just any old model, shimmering away, like memory itself? Or the vexed fantasy of a specific new love interest on Schlesinger’s part? And what are we to make of the painting’s title, Portrait of an Artist, in this context? Might the underwater swimmer be a wistful stand-in for the artist himself? Or is the real relationship in question the one between the artist standing outside the image, rendering it into being, and the pink-jacketed man now eternally removed on the far side of the picture plane?

This would prove to be one of the last in that particular series of double portraits, but, curiously, it was to point the way toward a fresh Hockney passion and perhaps the hinge moment of his career. There were all sorts of complications in the production of this second version of the image. For one thing, Hockney was no longer in California at the time, but rather back in London, so he had to travel to the south of France for the nearest approximation of such a sun-drenched pool. And because Schlesinger was no longer with him, he’d had to use a stand-in for his quick photographic studies of the scene in question. Back in London, Hockney had then had to ask his estranged lover to wear the pink jacket for a photo shoot in a nearby park. He’d also had to meticulously recalibrate the time of the shoot to match the shadow splay of the original southern shots.

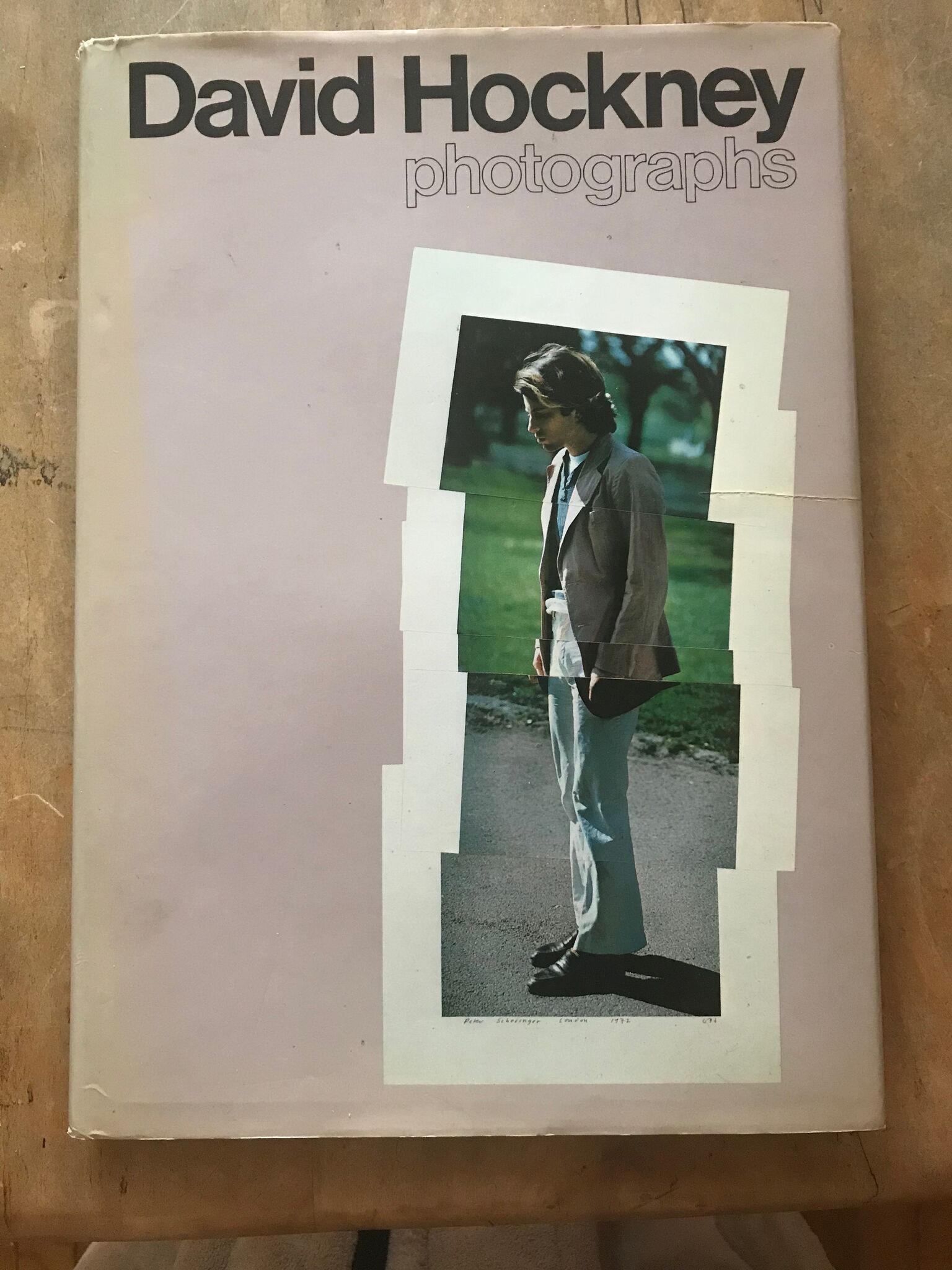

And the thing of it is that by then he’d come to understand that single photographic snaps of standing figures distorted the actual proportions, the figures being trapped in their inevitably projected one-point-perspective. He’d therefore begun stacking quick sequences of chopped-up details from the snapshots, an especially disconcerting procedure in this context, as was evident from the result (you don’t have to be Sigmund Freud to wonder about the third of those five shingled images).

Photo of the author’s copy of David Hockney Photographs (Lawrence Weschler)

The point is, there’s a direct through line from that shingled column of snapshots to the subsequent photo collages that would famously come to dominate Hockney’s career several years later and launch him off on an inquiry into the limitations of one-point photographic perspective, whose hegemony in European art over the past 500 years has come to constitute the focal point of much of his wider work ever since.

So, okay—the painting is important. As is its creator, all the more so since his recently concluded Tate-Pompidou-Met blockbuster retrospective. But what about that predicted price?

For starters, it should be noted that when it comes to assigning a fair and just monetary value to a work of art, any and every work is somewhere between worthless and priceless, and any specific numerical assignation beyond that comes under the category of comedy, as in Puck’s insight regarding the eternal folly of mere mortals.

Having said that, there is such a thing as a market, and the immediate price of any given work of art depends on what the current market will bear, a number that in turn depends on all sorts of variables. In the current instance, those variables include: the relative scarcity of such blue-chip works compared with the upsurge in the number of mega-millionaires from all over the world in a position to vie for them (including many new ones from Russia, China, and the Middle East, and not a few from the U.S., their balance sheets enhanced by their recent tax windfalls); the rise of contemporary art as a fungible commodity (perhaps no more precarious an investment than many of its alternatives, especially in the case of a record-setting work that then becomes even more valuable for being the one to set such a record); the seeming conviction among dealers and collectors that prices can only keep going up (although we all know where that sort of thinking leads); the ancillary value of the ownership of a work of art in validating or laundering the cultural credentials of its owners (not to mention, in the current market, a work of art’s value in actually laundering the monetary gains of some of its more shady international bidders); and so forth. The market simply is what it is.

And yet surely the main word summoned forth by the prospect of a single work of art by any living artist commanding these sorts of prices is scandal.The first and most obvious scandal is that there are not just dozens but hundreds of individuals with so much disposable wealth (quite a term, that, come to think of it) that they can afford to bid one against the other, lustily cheering at the prices as they climb higher and higher, in a world where millions go hungry and homeless, not a few in the immediate vicinity of the galleries and auction houses.

The lesser scandal is that the artist in question hardly ever partakes in the profits of such a sale—these purchases constitute transactions between idle millionaires, usually mediated by middleman dealers or auction houses (though to be sure, such transactions can help jack up that artist’s own prices in the future, which is its own kind of scandal in a hypercharged and often seemingly arbitrary winner-take-all art market, where only the top few percent of players can afford to make any kind of decent living).

And, finally, there is the scandal that such an iconic work of international culture will now be disappearing into the domain of a private individual (rather than living in public in a museum, because hardly any museums can afford to bid at such heights) or else into the vaults of some dedicated storage facility near the Frankfurt or Abu Dhabi or Shanghai airport, potentially not to be seen again in the flesh, as it were, for generations.