Convergences & Pillows of Air

CONVERGENCES

Following the publication of Everything that Rises in 2007, the McSweeney’s.net website hosted a contest in which readers could submit their own instances of such convergence phenomena and I got to choose my favorites and then respond (sometimes, for that matter, I posted my own). The full run of that eventually four-year run can be accessed here. Below are a few of the later entries from the original contest to get you in the mood.

Apoptosis: A Boom/Cancer Convergence

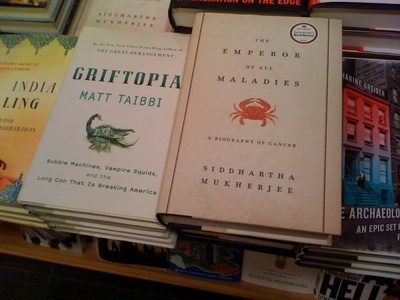

So, I happened to be in Posman’s, the independent bookstore at Grand Central, the other day, and noticed these two books stacked one beside the next.

Which is to say, Rolling Stone ace reporter’s Matt Taibbi’s Griftopia: Bubble Machines, Vampire Squids, and the Long Con that is Breaking America, and Siddhartha Mukherjee’s National Book Award-winning The Emperor of all Maladies: A Biography of Cancer. And I suspect that, like you, I couldn’t help but be struck by the similarity in the cover images. Which in turn got me to thinking about an op-ed piece Walter Murch and I contributed to the Los Angeles Times about a year ago (May 23, 2010), which I herein offer as a gloss on this particular not-so-innocent coincidence.

- - -

Economy: The Trouble With Bubbles.

“I can calculate the movements of the stars, but not the madness of men.”

— Isaac Newton, after losing the equivalent of $3 million in the financial catastrophe of the South Sea Bubble in 1720.

The word “bubble” just has an inescapably happy feel to it, conjuring up kids and parties and sudden iridescent poppings, screams of laughter, the giddy clapping of happy hands and an overall lack of consequence. That was fun; now where’s the cake?

Even more so when the word gets paired with “tulip” or “South Sea.” Where could the harm possibly be in such blithe and fragrant things? Certainly not in the words themselves: exotic petals, swaying grass-skirted maidens, spheres of trembling insubstantiality.

Things get a bit more pedestrian with the more recent dot-com and housing bubbles. But still, seriously, where’s the harm?

Well, to paraphrase Christopher Wren’s epitaph: If you seek its monument, look around you. The financial wreckage from this last housing bubble (that outbreak of “irrational exuberance”) is still being inventoried, and its consequences are considerably more serious than the wet smacking pop associated with the word itself. Nor was there any cake (unless it came in the form of those sweet bonuses handed out as party favors to the executive celebrants up and down Wall Street).

And yet, despite the economic damage of the last few years, we are repeatedly soothed by the innocence of the word “bubble” itself. Lulled by language, we’re invited to contemplate, with relative equanimity, simply getting to hear that fateful “pop” every so often, as the inevitable price to be paid for the market freedoms of the unregulated capitalistic system. Ah well: Kids will be kids.

But what if we were to conjure another metaphor? Perhaps a more apt analogy. Might it help rouse a more pertinent response?

Take, for example, the constantly surging froth of pre-cancerous cells in each of us. At any given moment, a rogue cell might somehow lose a sense of its place in the organism — that it is a liver cell, say — and instead believe itself to be alone in a hostile, plunderable environment. This is not surprising when you consider that there are 50 times more cells in a human body than there are stars in the Milky Way: 10 trillion versus 200 billion. Something’s bound to go wrong somewhere. Under such circumstances, the rogue cell’s raison d’etre becomes: “Defend. Survive. Dominate: Be fruitful and multiply.” And so it does, using the local environment — of the liver in this case — as a food resource to be exploited by whatever means necessary

For most of us, most of the time, this pre-cancerous froth never proves a problem because there is a regulatory agency — the immune system — that quickly identifies those rogue cells, reminds them who they really are and encourages them, as it were, to commit suicide, a process known as apoptosis. This fatal encouragement can come spontaneously from within the cell itself (suddenly recognizing its own roguishness) or from the surrounding healthy cells (a neighborhood group enforcing community standards) or from immune-system “police” cells patrolling the body as a whole. This process is happening constantly, is part of the normal functioning of the healthy organism and gets accomplished without any awareness on our part.

Trouble occurs when, for some reason, the normal functioning of apoptosis breaks down — the cell’s own compunction fails to kick in, the surrounding cells prove too weak or are otherwise distracted, the local regulatory agency is asleep at the switch — and the cell in question cannot be persuaded to end its life. Instead, it multiplies exponentially, becoming the seed of a cancerous tumor. Only now, at a certain threshold, does the greater organism become aware of it, and an existential conflict ensues.

The tumor is now set against the interests of the greater organism of which it was once a part. Its brief is to flourish at all costs, to thrive at the expense of the surrounding healthy tissue. Followed to its inevitable conclusion, this means doom for both the host and the tumor. Though, of course, until that dreadful “pop,” the tumor doesn’t see it this way.

What would it be like to think of the travails of the wider economy, the coursing flow of capital through the body politic, in those terms? (It’s worth remembering that when the sainted Adam Smith first began to ponder the circulation of capital in the seminal explorations that would lead to his monumental “Wealth of Nations,” he was quite consciously modeling his inquiry on William Harvey’s investigations into the circulation of blood a few generations earlier.)

What if, instead of that playful word bubble, we tried something a bit more accurately descriptive when growth at any cost became the goal. Say, “tumor”: “the dot-com tumor,” “the subprime tumor,” “the derivatives tumor.”

Would anyone seriously gainsay the highest possible vigilance over the proper functioning of their own body or doubt the need for strong regulation? Who, facing the prospect of a tumorous outbreak or living with a body demonstrably prone to such outbreaks, would entrust that body to a band of physicians blithely committed to laissez faire regarding these fatal bubbles of flesh?

Words matter. Metaphors frame thought. Pay them heed and tend them well.

Bearded Ladies Breastfeeding

So I recently happened to be in Madrid for a few days and took advantage of that fact to stroll once again through what is arguably the world’s greatest collection of old masters paintings, that of the Prado, which is where I came upon the astonishing triple-portrait above, dated 1631, by the then-Naples-based Spanish tenebrist master Jusepe de Ribera (apparently on loan from a museum in nearby Toledo).

As you’ll doubtless agree, it’s a hard image to shake, and back at the hotel I took to trawling the internet for background information, which is how I came upon the following entry from University of Maryland professor Jeff Matthews on his “Around Naples Encyclopedia” blog:

The title of this painting is simply Bearded Woman and it is from the year 1631. The painting is now in the permanent collection of the Museo de Tavera in Toledo. The subjects were husband and wife, Felix and Magdalena Ventura. Even before the painting, Magdalena Ventura was famous. She was not really from Naples, but rather from somewhere in the nearby Abruzzi. She was already a grown woman with several children before her beard started to grow in thick and full like a man’s beard. When the Duke of Alcala, the Spanish viceroy of Naples at the time, heard about her, he invited her to come into the big city and sit for a painting by de Ribera, the Duke’s own court artist and one of the leading painters of the time. Magdalena’s fame spread such that she was mentioned in court correspondence throughout Italy, reflecting perhaps all of our lasting fascination with weirdness. The Duke and his quack medicos certainly weren’t up on such things as androgen excess or perhaps the rare genetic disorder known as hypertrichosis; they just thought, Holy Cow, a bearded lady. (I think the expression “Holy Cow” comes into English from India; it doesn’t exist in Italian or Spanish, so the Duke probably said something else.) But enlightened minds such as yours and mine are, indeed, up on such things as androgen excess and hypertrichosis, and we still think, Holy Cow, a bearded lady.

Holy Cow, indeed. And yet it seemed to me somehow that there was more to the uncanny power of this image than merely bovine hirsute mama associations.

And then I recalled a parallel set of unsettling visual provocations from back in my own days reporting Poland’s transition from out of Communism for the New Yorker, in this instance from the magazine’s issue of December 11, 1995, where I profiled Jerzy Urban, the roundly despised and just as roundly despising Jewish government press spokesman of Warsaw’s prior martial law regime. Mr. Urban had gone on to become one of the country’s richest men, following the transition, by founding the deliriously scandalous gutter rag, Nie (which is to say, “No!”), part Screw magazine and part Canard Enchaine, the venue for a whole slew of outrageous stunts. As I reported at the time (the piece is also included in my collection, Vermeer in Bosnia, though unlike there, in what follows I intersperse the relevant imagery):

Perhaps Urban’s favorite “happening,” though, was the time he conned the newly reopened Warsaw luxury Hotel Bristol into getting itself certified kosher [the better to cater to the exponentially expanding holocaust tourism trade]. He pulled out an issue of Nie and, turning to a photo spread, showed me how an actor—or, rather, a young actress—had been disguised as a hunched, bearded, and bedraggled old rabbi and had been driven to the hotel in Urban’s Jaguar; and how the “rabbi” had thereupon dragged the hotels’ prim-and-proper female business manager all around the establishment, peppering her with arch questions.

“It was great,” Urban declared. “We made a complete fool of this business-manager lady.” (“Yeah, she’s probably committed suicide by now,” one of my friends subsequently commented. I asked what she had done to deserve such treatment. “Oh, her just being a woman is generally provocation enough for Urban,” my friend replied.) Urban continued, "And here the rabbi is signing the certificate—look at the manager, look at how tense she is.

It’s hilarious. And then here we have the rabbi being escorted back to my Jaguar, and then here…" Urban was speechless with satisfaction: the last picture showed the “rabbi” back in the Jaguar, a few blocks away, her black coat removed, her white shirt opened, her beard gingerly pulled aside as she breast-feeds her child. The photograph was captioned “Rabin z dzieciatkiem,” the latter being a word for child used almost exclusively in the expression “Madonna and Child.” It was a combination of image and caption almost precision engineered to fry every nationalist circuit in the Polish imagination. Urban smiled broadly and declared his labors good.

Which in turn has gotten me to thinking about that Ribera image again.

Because that isn’t just some bearded lady breastfeeding her baby. That’s a bearded lady who looks very much like a rabbi—of the sort Rembrandt was painting during the same period, as in this instance, now at the Hermitage in St Petersburg, from a few decades later (1654, note the cap):

My good friend, the poet Stanley Moss, himself a longtime distinguished dealer in Old Master paintings, tells me I’m crazy to be advancing this hypothesis—that is, that there is something oddly Jewish about the way de Ribera has chosen to portray his breastfeeding bearded lady. But I don’t know. And it’s not as if it wouldn’t have been as loaded a depiction in its time (1631) as Urban’s was in his place: a Spanish painter, after all, in the wake of the expulsion of the Jews from Spain in 1492, and the centuries thereafter of Inquisitional anxiety about the persistence of secret conversos in the country’s midst (with all of Europe, for that matter, still wrestling with its Jewish problem: The Merchant of Venice, 1598; Don Quixote, 1605 and 1615; Spinoza born the very next year, 1632)—portraying a bearded rabbina, that is, Madonna-like, breastfeeding her infant, with her haggard husband gazing on, Joseph-like, from the shadows.

It’s just a really odd painting, is all I’m saying.

Carnival of Convergences No. 8

By Carol Rosofsky, Eric Lidil, Lawrence Weschler and Matt Haber

- - - -

Bangkok and the Noonday Sun

Submitted by Matt Haber

- - -

Protesters in Bangkok, 2010.

Photo: Adrees Latif/Reuters.

- - -

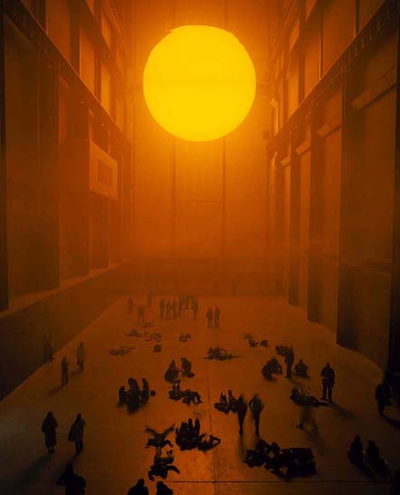

Olafur Eliasson’s 2003 installation “The Weather Project.”

In Turbine Hall of London’s Tate Modern.

- - -

Tubaned Epiphanies

Submitted by Carol Rosofsky

- - -

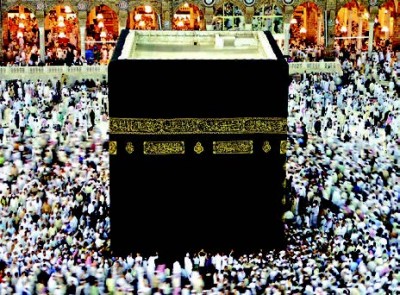

Hajji Abdul Zahir, far left, the district governor of Marja, oversees payments by the Marines to Afghans in the region. Photo by Moises Saman for the New York Times.

- - -

Rembrandt’s Feast of Belshazzar (c. 1635).

- - -

The Bagmaker

Submitted by Eric Lidil

- - -

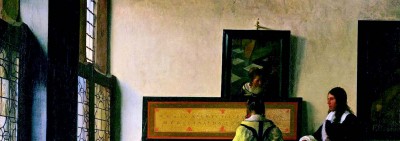

Vermeer’s The Lacemaker (1669).

- - -

Louis Vuitton ad in the November 30, 2009 issue of the New Yorker.

Mr. Lidjl notes that, just as in Vermeer painting where (as Weschler pointed out in Everything That Rises), the lacemaker is gazing down on the tight crisp V of thread couched in her M-like hands, hence spelling out the author of her own existence, VM—so in this ad, the bagmaker is gazing down on an L of thread spread atop that inverted V-clamp, hence LV, the very sponsor of the ad in question.

- - -

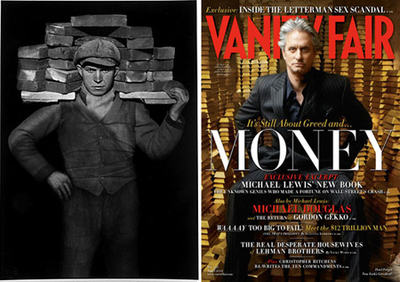

Bricks

Submitted by Matt Haber

- - -

Left: August Sanders’ Bricklayer (1928).

Right: April 2010 Vanity Fair cover, photographed by Annie Leibowitz.

Mr Haber’s second winning entry in the current carnival.

Mr Haber notes: “The cover of the April 2010 issue of Vanity Fair (shot by Annie Leibovitz) strikes me as an homage to August Sanders’ Bricklayer (1928). Leibovitz has appropriated thousands of fine art images over the years, so I have to assume it’s intentional, but recasting an image of a proud working stiff from Weimar, Germany as Michael Douglas playing Gordon Gekko, the pampered Wall Street crook is a bit, um, well, rich.”

- - -

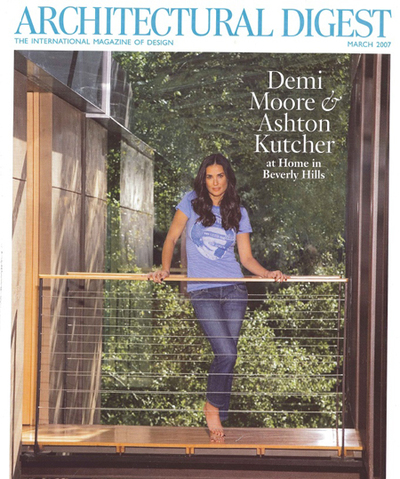

Demi on the Clamshell

Submitted by Lawrence Weschler

- - -

Demi Moore on the cover of the March 2007 issue of Architectural Digest.

Botticelli’s Birth of Venus (1486).

- - -

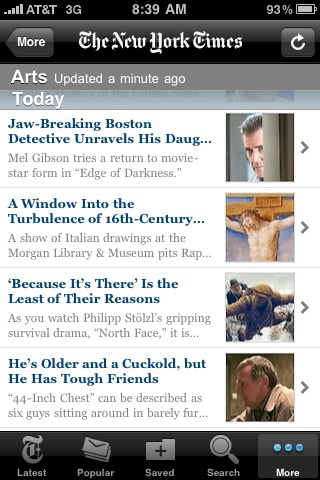

Eerie Premonition

Submitted by Matt Haber

- - -

When Mr Haber submitted this catch off the January 29, 2010 New York Times website, his third winning entry in the current carnival(!), he was presumably calling attention to the droll way Passion of the Christ’s Mel Gibson peers from behind the cross-like doorframe as played off the image below that, and how that image in turn played off the crucified-like stance of the guy in the one below that. But today the fourth image in the series, or rather the title of the review it illustrates, plays all the more uncannily off Mr. Gibson’s recent travails—or should we say, Passion?

“We are the Son” by Danny Erker

Ever since I stood face to face with them in Madrid’s Prado Museum, I’ve been completely creeped out by Goya’s Pinturas Negras. Easily the grossest in that series is Saturn Devouring One of His Sons. In it, the Spanish master depicts the terrifying image of a deity so drunk on power and mad with fear that he eats his own. Cloaked in black, his white knuckles emerging in a tenebristic fit of cannibalism, Saturn himself is only slightly less revolting than the notions he conjures up: the mythic father, epitomic manifestation of patriarchal protection, so enslaved by his will to dominate that he’s willing to squander the fragile potential of youth in a gluttonous fit to satisfy himself.

Thank God it’s just a painting.

Weschler Responds

Amen to that, Daniel. Amen to that.